Deeper understanding of the icy depths

Research Press Release | October 20, 2022

Scientists have uncovered new details of how ice forming below the ocean surface in Antarctica provides cold dense water that sinks to the seabed in an important aspect of global water circulation.

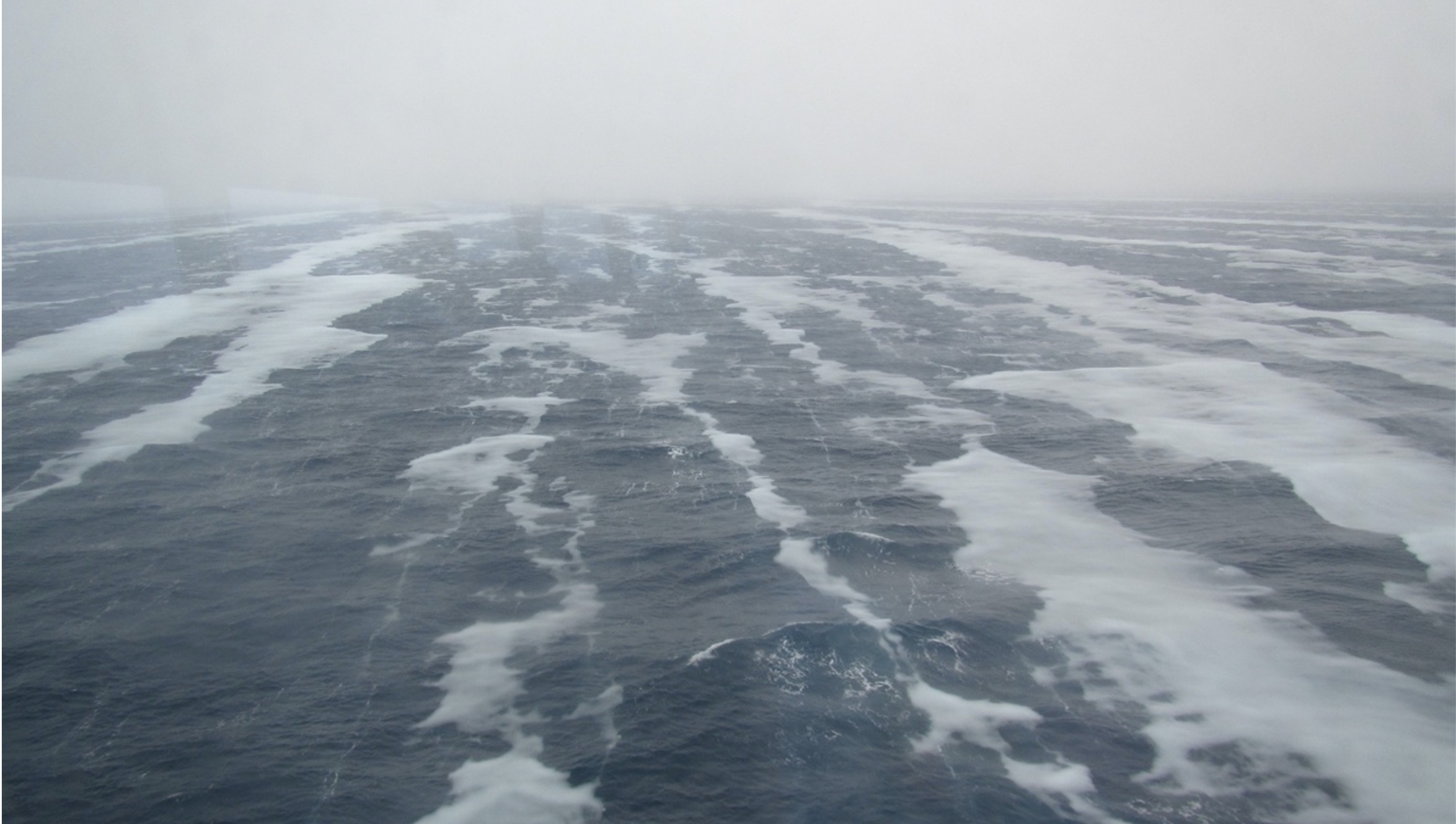

Frazil ice formed below the ocean surface drives the generation of cold dense water. (Photo: Masato Ito)

The results, published in the journal Science Advances, come from a team at the Hokkaido University’s Institute of Low Temperature Science, its Arctic Research Center, and the Faculty of Fisheries science, working with scientists at Japan’s National Institute of Polar Research and Aerospace Exploration Agency.

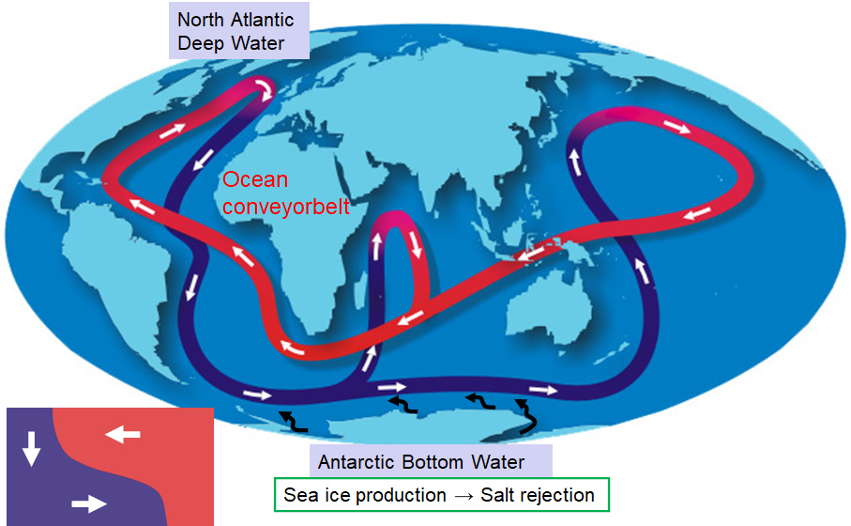

The seas around Antarctica, where a large amount of sea ice is formed, are central to global ocean water circulation, linking the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. When sea ice is formed, it rejects salt, therefore leaving dense, cold water that sink to the seabed. This water, called Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), is the coldest and densest water mass in the global circulation, flooding across most of the deep seafloor known as the global abyss. Since the global ocean circulation influences the global climate, it is important to understand the mechanism of AABW formation and how the formation will be impacted by global warming.

The cold, dense water formed around Antarctica sinks to the seabed, driving global ocean circulation. (Kay I. Oshima)

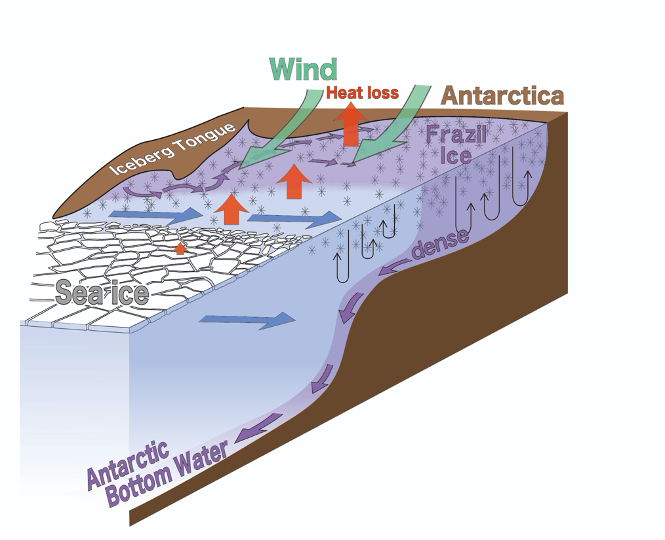

“We found surprising new results about the form of sea ice growth in a key AABW production site, close to Cape Darnley in Antarctica, with potentially wide implications for other areas,” says Kay Ohshima of the Hokkaido team. He explains that satellite monitoring and data from moored sensors in the ocean revealed the importance of underwater ice called Frazil ice in producing dense cold water. This ice forms beneath the surface when water is cooled to below its freezing point by the cooling effect of the strong wind and turbulent conditions. The cooling can occur to surprising depths of 80 metres or more.

Around the coast of Cape Darnley, frazil ice forms efficiently under the sea surface particularly due to the strong wind and resulting heat loss. When Frazil ice forms, it generates cold, dense water which sinks to the seabed forming Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW). (Kay I. Ohshima et al. Science Advances. October 19, 2022)

Their key significance is that they involve an area where water is cooled by strong wind from severely cold Antarctica, especially in open water areas within the pack ice called polynyas.

“It is important to learn that such a major process is occurring underwater, revealing an aspect of the circulation system that has been at least partially obscured from view,” Kay says.

The researchers also suggest that the frazil ice could incorporate the sediment at the sea bottom and release it as the ice melts. This may yield new understanding of the circulation of nutrients that fertilize plankton to influence the general biological productivity of Antarctic waters.

“Our next step is to incorporate these new processes into understanding of Southern Ocean biogeochemistry and carbon circulation, which will require significant new fieldwork and research,” Kay concludes.

Original article

Kay I. Ohshima et al. Dominant frazil ice production in the Cape Darnley polynya leading to Antarctic Bottom Water formation. Science Advances. October 19, 2022

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adc9174

Funding:

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aids for Scientific Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan (20221001, 25241001, 17H01157, 17H06317, 20H05707, 20K20933, 21H04931); the Science Program of Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (project no. AP05); the Global Change Observation Mission Water 1 of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (PI nos. ER2GWF404 and ER3AMF424); the European Space Agency (project ID 6130); the National Institute of Polar Research through Project Research (KP-303); and the Joint Research Program of the Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University.

Contacts:

Professor Kay I. Oshima

Institute of Low Temperature Science

Hokkaido University

Tel: +81 11-706-5481

Email: ohshima[at]lowtem.hokudai.ac.jp

Sohail Keegan Pinto (International Public Relations Specialist)

Public Relations Division

Hokkaido University

Tel: +81-11-706-2185

Email: en-press[at]general.hokudai.ac.jp