Meteorites: Message-bearers from 4.6 billion years ago

Research Highlight | March 29, 2019

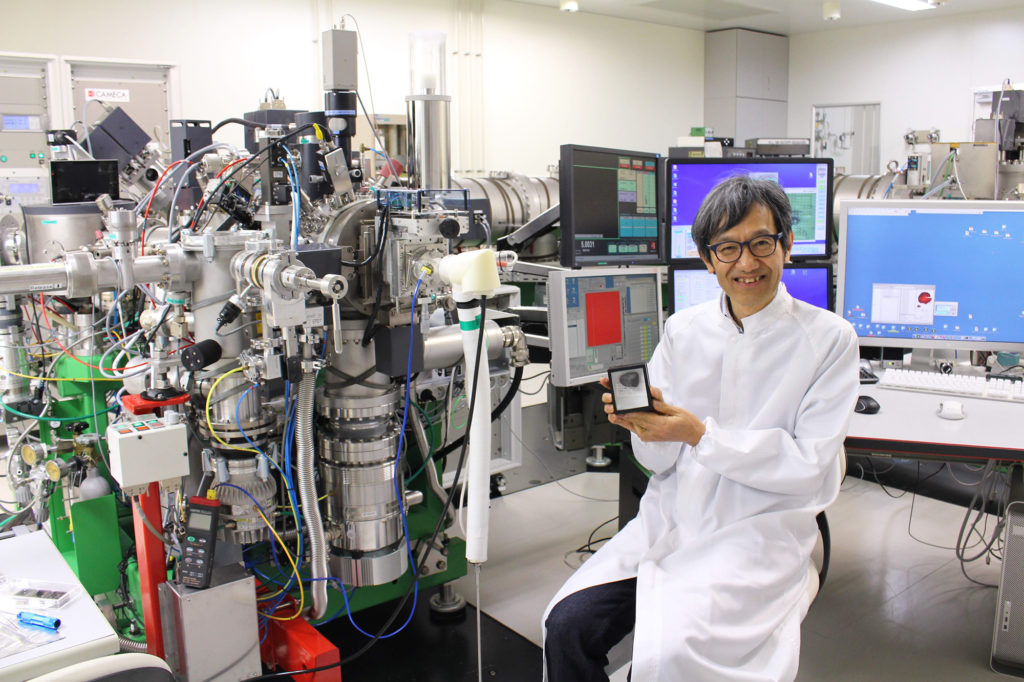

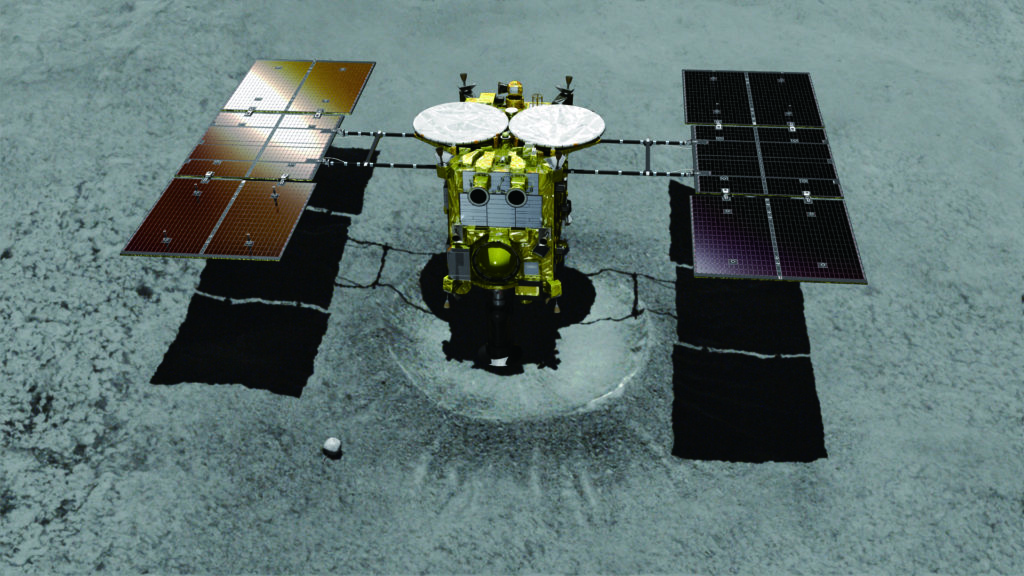

Hayabusa, a robotic spacecraft developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), returned to Earth in June 2010 after taking a sample from a small near-Earth asteroid named 25143 Itokawa. Professor Hisayoshi Yurimoto at the Faculty of Science, a member of the project is now analyzing the sample to find clues for elucidating how the solar system was born 4.6 billion years ago. He is also preparing to analyze a sample from Hayabusa2, which is scheduled to return to Earth in 2020 after collecting a sample from another asteroid, Ryugu, in February 2019.

Yurimoto is a born scientist. He has had a keen interest in science, especially beautiful minerals, ever since he was young. “I was so elated when I found quartz in a nearby mikan tangerine field,” Yurimoto said with a grin. Yurimoto researched minerals and obtained a doctor’s degree in the study of peridots, a green transparent variety of olivine often used as semi-precious gems. Olivine is found in lava and meteorites.

A turning point came more than two decades ago when Yurimoto was around 30 years old. During a meeting with a meteorite specialist, Yurimoto learned that meteorites contain minerals that are not found on Earth. More specifically, some minerals have isotopic ratios different from that of substances on Earth. Isotopes — two or more forms of the same element that contain equal numbers of protons but different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei, thus differing in their mass — exist in a certain ratio in elements on our planet.

“I was astounded to discover a meteorite’s isotopic ratio was different from the projected figure even though minerals in the meteorite were formed based on the same established laws of physics and chemistry,” Yurimoto said, explaining why he started focusing his research on meteorites to unravel the origin and evolution of the solar system. In those days, however, meteorites were hard to come by in Japan. Yurimoto proceeded with his research by borrowing samples from the aforementioned specialist. He also started developing an isotope microscope, a one-of-a-kind device weighing 10 tons, to unlock the mysteries enveloping the isotopic ratio in meteorites. The huge microscope, which was completed after 20 years of research and development, enabled researchers to distinguish isotopes of the same element in meteorites.

Yurimoto’s group used this isotope microscope to analyze the sample from Itokawa. His group examined the isotopic ratio of oxygen, the most abundant element in meteorites, which has three kinds of isotopes. The results showed the isotopic ratio in the sample was the same as that of ordinary chondrites, which account for 80 percent of meteorites that fall to Earth, demonstrating that meteorites are asteroid fragments and contain vital information from the time when the solar system was born. This finding was reported by the media and fueled discussions around the globe.

It is possible to deduce the pressure, temperature and time required to form meteorites by examining meteorites with the isotope microscope. “We are trying to figure out how the mysterious conditions in meteorites were created, based on isotopic microscopic analyses,” Yurimoto said, referring to the different isotopic ratios. “There are various theories about this. Some researchers suggest it is a result of lightening in space, and others point to the effects of collisions between celestial bodies. Nobody knows for certain. It is difficult to think about a phenomenon nobody has seen, but I’d definitely like to unlock that mystery.”

Use of the microscope is not limited to space science. As it is suitable for examining molecular movements, the microscope is used for research in fields including medicine, biology, agricultural science and engineering. “It is interesting to talk to many researchers in different fields who would like to use the microscope,” Yurimoto said. “Doing so sometimes has led to joint research with my team.”

Yurimoto’s curiosity about the unknown has not dimmed since he was looking for pieces of quartz as a boy. He is determined to decipher information hidden in meteorites and the original materials that created them, which Hayabusa collected from Itokawa. Driven by his unlimited curiosity that culminated in the development of a groundbreaking device, Yurimoto’s ultimate goal is to take a glimpse into a world nobody has seen before.