Spotlight on Research: A step towards preserving the Ainu language

Research Highlight | April 11, 2017

The Ainu people are the indigenous population of Hokkaido, Sakhalin and the Kuril islands. Having suffered a great deal of discrimination in modern history, there have been many recent efforts to preserve Ainu culture and its endangered language. The first law to protect the rights of the Ainu people was established in 1899, although the name of that law (“The Former Savage Preservation Law”) as well as its historical evaluation are now controversial. In 1997 came the “New Ainu Law,” and in 2005 Hokkaido University established its Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, which was created to deepen our understanding of the culture, as well as to increase awareness and appreciation of it.

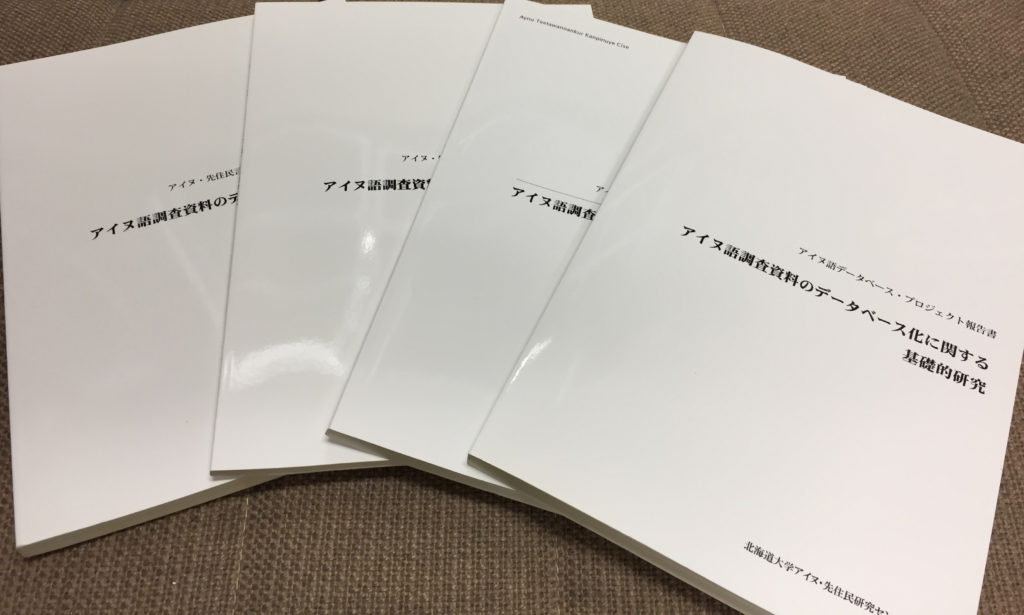

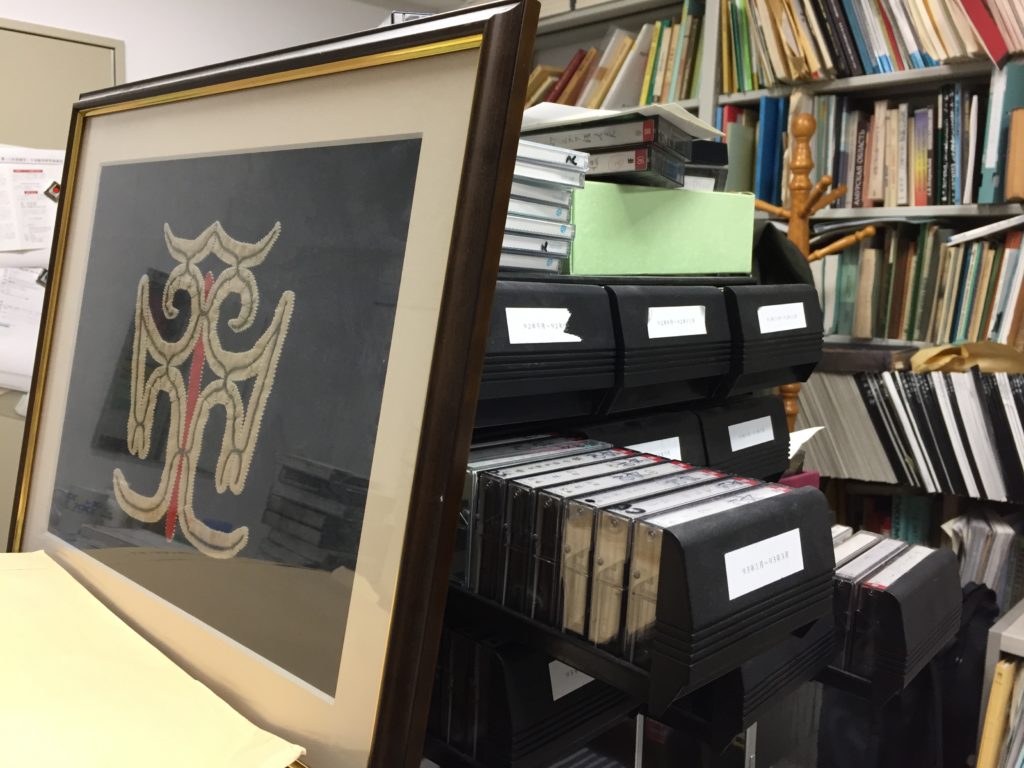

Professor Sato Tomomi, an affiliate of the center, is an example of someone involved in preserving Ainu culture, especially its language. Specializing in linguistics and the Ainu language, he estimates that most speakers of the language are of an elderly age. Although this makes it increasingly more difficult to conduct research about the Ainu language, Professor Sato has yet to fully analyze all of the recordings he has on file. It is his hope that his studies will be of use to people looking to learn the Ainu language; and indeed in 2008 he published a book titled “The Foundation of Ainu Grammar” for just that purpose.

For most of its history, Ainu was an unwritten language, and other than a few notable occasions (such as the アイヌ神謡集 “Collection of Ainu Mythologies” published in 1923) the language was not properly recorded in writing until fairly recently. For this reason, there is no set orthography in which Ainu should be transcribed. It is usually written either in Roman letters or Japanese katakana, but as Professor Sato explained – perhaps it is more appropriate to use Roman letters since it is a more neutral way to portray the language, whereas a transcription into Japanese katakana may in a way be relating it to the Japanese language.

Not unlike studying languages still widely spoken, analyzing the Ainu language gives us an insight into the thought processes and mindset of the Ainu people. For example, word structures in Ainu are usually quite complex. K-e-yay-ko-tuyma-si-ram-suy-pa in Ainu means “I’m thinking about…” However, a direct translation into English would actually be “I swing my mind to distant places many times by myself about something.” As a native English speaker, to me this conjures up the image that Ainu people truly do think about something when they say that – whereas in English words are too often tossed into conversation without really thinking about what was just said.

The lexicon of the Ainu language only begins to touch upon the subject, Professor Sato’s recent research surrounds the linguistic phenomenon of “noun incorporation.” Noun incorporation is the combination of a verb and a noun to create a compound verb. An example in English would be the word “to baby-sit.” Noun incorporation is incredibly uncommon in English (and also relatively rare in Japanese), but this is not the case for the Ainu language. Simple examples of this include cep-koyki – “fish catch” – or more naturally “to catch fish.” As mentioned before, Ainu words are often complex and full of imagery. An example of this is sir-pirka, which is also an example of noun incorporation and means “the surroundings are favorable” – or simply “it’s fine.” The rich imagery of the language is further exemplified by the incorporated verb teke-pase – “(his) hand is heavy” – meaning “he moves slowly because of his age.” This last example is also worthy of note since it contains the nominal stem, teke “one’s hand,” which has its possessor on the outside of its grammatical element. This type of linguistic construction is called “morphological stranding” and is very rare for a language to have.

Although previously considered a “primitive” language, it is by no means such from a linguistic point of view. In Professor Sato’s words:

Language can provide us with strong empirical evidence that human beings are the same in their basic capacity and must not be discriminated according to their ethnicity. But even today, outside linguistics, and partly even inside linguistics, there still remains strong prejudice and a discriminating attitude to unfamiliar minor languages and cultures.

The intricacy of the Ainu language in turn highlights the complexity of Ainu culture. Subsequently, it draws out the diversity of culture in Hokkaido, showing that Hokkaido too has a rich history worth re-discovering.

Researcher details

Professor Sato Tomomi

Professor of Linguistic Sciences

Faculty of Letters

E-mail: tomomis[at]let.hokudai.ac.jp

Author: Dr. Katrina-Kay Alaimo