Spotlight on Research: Is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting students’ stress level?

Research Highlight | October 23, 2020

An expert in developmental processes in teenagers, Associate Professor Hiromichi Kato of Hokkaido University’s Graduate School of Education has been observing children within the age range of puberty, roughly from 10 to 17 years old. The psychological characteristic of children within this age range is the susceptibility to problems, from depression to delinquency.

According to Prof. Kato, the general Japanese society respects conformity and community. Japanese teenagers are inclined to seek this communal sense by establishing good relationships with their peers, rather with their family members. This social need, more often than not, overpowers academic achievement within these teenagers’ priority list.

With such a perspective, it is only natural most people assume that the school closure, most notably for middle schoolers, would be hard for these students. The coronavirus pandemic had forced most schools to close and halt their usual activities. By observing a middle school in the Tokai region, Prof. Kato looked deeper into this issue to confirm the suspicion on students’ stress levels. Yuejiang Hou, a 3rd year PhD. student from his research laboratory, assisted in the data analysis.

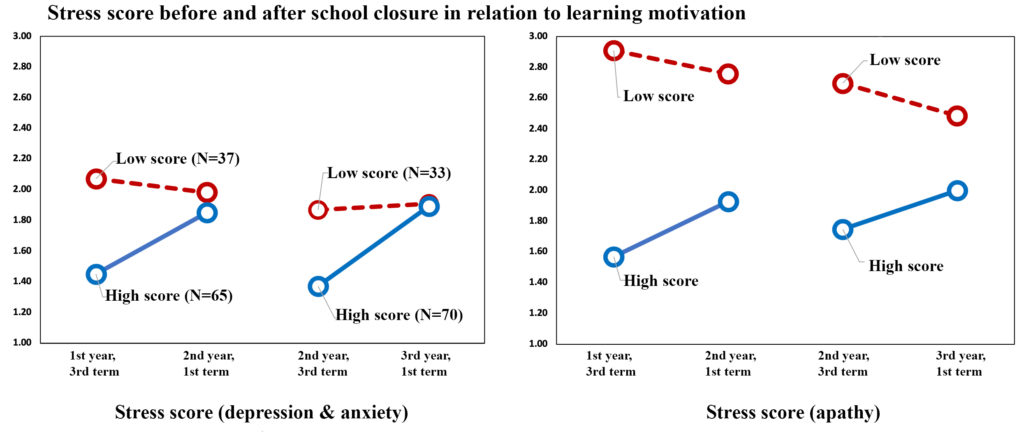

The researchers have been gathering data from over 200 middle school students (current second and third year) for over a year, including during the school closure period that covered roughly three months from March to May 2020. Each student is asked to participate in a series of questionnaires in which they rate the statements from scale one (the least applicable) to five (the most applicable). The given statements are related to their feelings and motivation to study, such as: “I am looking forward to going back to school” and “I am having a hard time concentrating”. The findings are separated into two types: one concerned with depression and anxiety, the one with apathy. Despite the rising average level of stress, the general result didn’t show a spike.

“The accumulated stress level may have seen a rise, but it is not at all alarming. There are numbers of factors that could have contributed to this increase and it is different for each individual,” explained Prof. Kato.

A graph showing middle school students stress scores before and after school closure. (Study by Hiromichi Kato, et al.)

The different individual factors come in many forms. For instance, students who enjoyed studying at school would express a bigger desire to go back to school, whereas those who didn’t enjoy school-learning in the first place might feel better at home. Even for those who are highly sociable among their peers, the current technology has provided ways to reconnect with friends, e.g., video games, among many others.

While the finding shows a relatively safe stress level of students, Hou mentioned that there are certain new subjects that come to light, one of which was absenteeism or the reluctance to go to school. Absenteeism often occurs in Japanese schoolers in teenage years, most frequently accompanied by certain difficulties at school. Since the school has been reopened, 40% of schoolteachers reported an increasing number of school-skippers.

The fear of coronavirus infection might have played a role in this increase. Prof. Kato and Hou also compared the data with another middle school located in Hokkaido. The result shows that there is a higher number of students in Hokkaido expressing worry to go back to school, considering the possibility of getting coronavirus infection. This is where Prof. Kato and Hou focused their concern on types of teachers’ responses on measures against COVID-19.

They also conducted another separate research that shows a diverse response of teachers in regard to this pandemic. Some teachers are serious and worried, while some others feel more optimistic and relaxed. “We still see cases in which schools already have implemented these protocols, such as the obligation to wear masks and wash hands; but the execution is still not enough, namely the lack of social distancing during recess,” said Hou.

Out of concern, Prof. Kato added the importance of having discussions to have an aligned perspective in facing the pandemic, not just among instructors, but also between instructors and students. The personal differences in response to COVID-19 and school closure, in fact, serve as good starting points to find the solutions of unanswered problems through discussion.

Prof. Kato, along with Hou, is still looking into many other aspects of juvenile psychological state, mostly about self-esteem and the aforementioned absenteeism. In relation to the ongoing pandemic, both are trying to look at how the children are spending time in coping with stress.

Researchers details:

Associate Professor Hiromichi Kato

Hokkaido University

katou[at]edu.hokudai.ac.jp

Hou Yuejiang (PhD, Student)

Hokkaido University

yuejiang_hou[at]eis.hokudai.ac.jp

Written by Aprilia Agatha Gunawan