Spotlight on Research #24: Does this surgical mask make me look cute?

Research Highlight | February 02, 2016

How wearing a mask affects perceived attractiveness

Walk down any street Japan and you could be forgiven for thinking you have stepped onto the set of a medical disaster movie. Surgical masks are frequent accessories, worn to protect against colds, allergies or even to conceal a lack of make-up. Yet for Jun Kawahara1, the mask also has an additional effect.

“Many students wear masks while I teach. I don’t like this, since I can’t tell if they understand the class.”

Concealing part of your face under a mask obscures many social cues, including intention and emotion. From Kawahara’s research field in the psychology of human attention, this led to the question of what effect the mask had on our perception of the wearer.

With a trend for Japanese women to don masks when not wearing make-up, Kawahara focussed on the mask’s impact on attractiveness. A database of 66 male and 66 female faces was divided into ‘low’, ‘middle’ and ‘high’ categories of attractiveness using the opinions of 31 student volunteers. Sets of 22 faces either with or without masks were then shown to different groups who repeated the rating.

When the results rolled in, those in the ‘high’ category for attractiveness were perceived as far less attractive while wearing a mask. Meanwhile, the ‘low’ category group saw no perceptible difference, with the ‘middle’ category showed a small drop. In short, the more attractive you were, the less attractive the mask made you appear.

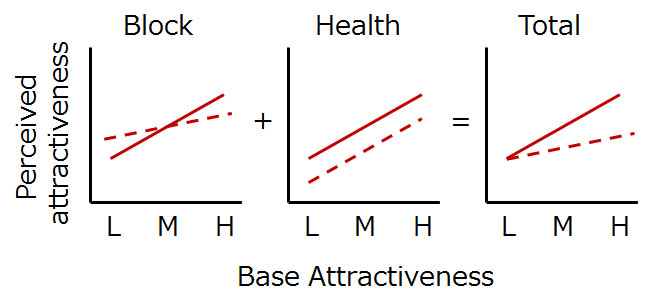

Kawahara’s hypothesis is that the mask affects two main factors linked to attractiveness. The first is health. Wearing a mask is often a sign that the person is unwell. It also has associations with medical facilities such dentists and hospitals, none of which are particularly positive. This affects everyone equally and reduces the perceived attractiveness of every face.

The second factor depended on the individual. While attractiveness is difficult to precisely quantify, several features are generally deemed negative. These include cracking lips, pimples or other skin blemishes. A person suffering from these inflictions might benefit from concealing this with a mask. On the other hand, a person with flawless skin would lose this advantage by hiding their face.

Combining these two effects leads the mask having a detrimental effect that increases with a face’s attractiveness. It was precisely the opposite of the widely-held opinion that a mask was better than no make-up.

To test this result further, Kawahara performed the experiment using a notebook rather than a surgical mask. The same fraction of the face was obscured, but the covering object was clearly different. The result was a smaller drop in perceived attractiveness for the ‘high’ attractive category and a slight rise in the perceived attractiveness for the ‘low’ and ‘middle’ groups. The reason was that a notebook has no health connotations, removing that factor from people’s judgement.

The predicted effect of wearing a mask. Solid line shows the perceived attractiveness of faces with a low (L), medium (M) and high (H) attractiveness level. The dashed line is the result when a mask is worn. ‘Block’ is the impact of obscuring part of the face while ‘Health’ is the perception of a person’s well being.

When presenting this work at a conference in Japan, the results caught the eye of the surgical mask manufacturer, Unicharm. After talking with Kawahara, the company decided to produce a new mask; one that was pink. The idea was to off-set the negative effects of obscuring the face with a pleasing colour. Such a theory was not implausible; previous research had indicated that clothing colour plays a large role in perceived attractiveness. But did this hold when using a mask?

Kawahara selected a group of female faces to test this theory. He found that the pink colour bypassed the association with bad health, giving all categories a boost compared to the white mask.

The conclusion is that if you are sick, but do not want to look it, select a pink mask. However, it is very hard to beat your own face.

[1] This research was conducted in collaboration with Dr. Yuki Miyazaki of Chukyo University

Researcher details:

Jun KAWAHARA

Specially Appointed Associate Professor

Human Sciences / Psychology

Graduate School of Letters

E-mail: jkawa@let.hokudai.ac.jp

Tel: +81-11-706-4154

Extra Information:

Publication: Miyazaki & Kawahara, ‘The Sanitary-Mask Effect on Perceived Facial Attractiveness’, Japanese Psychological Research (Vol.58, No.3)

—

Author: Elizabeth Tasker