The impact on oceans, organisms, and society explored from the bottom of glaciers

Research Highlight | December 07, 2022

This article first appeared in the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change.

15 questions for climate change researcher Dr. Sugiyama (with subtitles).

Shin Sugiyama

Professor, Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University

(Photo by Manami Kawamoto)

Professor Shin Sugiyama of the Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University, who studies glaciers and ice sheets in Antarctica, Greenland and mountainous regions, lives by a motto: visit the field sites in person and make observations. He is also interested in understanding the impact of climate change on the lives of local people. He talked about how the glaciers, ice sheets, and people’s lives are changing in cold regions.

Bowdoin Glacier in Greenland, where the glacier terminus flows into the sea (Photo by Shin Sugiyama, 2013)

Melting glaciers and ice sheets on the Earth

When snow accumulated on land is compressed by its own weight, it forms large blocks of ice that slowly flow together, called a glacier. Among these, large glaciers that cover land on a continental scale are called ice sheets. Ninety percent of the glaciers and ice sheets on the Earth are located in Antarctica and about ten percent in Greenland. In recent decades, the melting of these glaciers and ice sheets has been accelerating, especially in Greenland. It has also become clear that even the Antarctic ice sheet, which was previously thought to be stable, has been losing ice in recent years.

Importantly, when large amounts of meltwater flow into the ocean, they change the circulation of seawater, which in turn changes the circulation of materials and heat in the entire ocean, affecting the global climate and marine ecosystems. In addition, the ground exposed by melting glaciers is unstable and prone to erosion and landslides.

Given the importance of these events, my research is focused on uncovering the mechanisms of melting glaciers and ice sheets, as well as making future predictions.

Qaanaaq, a small village in Greenland where Prof Sugiyama and his colleagues go for research (Photo by Shin Sugiyama, 2012)

Things that can only be observed in the field

Nowadays, we can study glaciers and ice sheets through observations from space using satellites and by computer simulations. However, it is still important to go to the field, observe the landscapes, and collect the data that can be obtained only in the field. In particular, I am currently working on a research project in which I use hot water to dig a hole of about 15 cm in diameter from the top of a glacier, and actually look down and observe how the glacier borders the ground several hundred meters below; this cannot be observed via satellite or simulated. In addition to Antarctica and Greenland, we also go to Patagonia in South America to compare the mechanisms of changes in glaciers and ice sheets in different regions.

Unlike Antarctica, Greenland is inhabited, and warming climate causes problems such as flooding and landslides. On the other hand, it is not all bad for the locals, as the harbor can remain open for a longer period thanks to the reduced sea ice.

The study of glaciers and ice sheets is broadly linked to the fields of atmospheric, meteorological and oceanic sciences; when considering their impact, it is also linked to the field of sociology.

Accelerated melting of glaciers and ice sheets

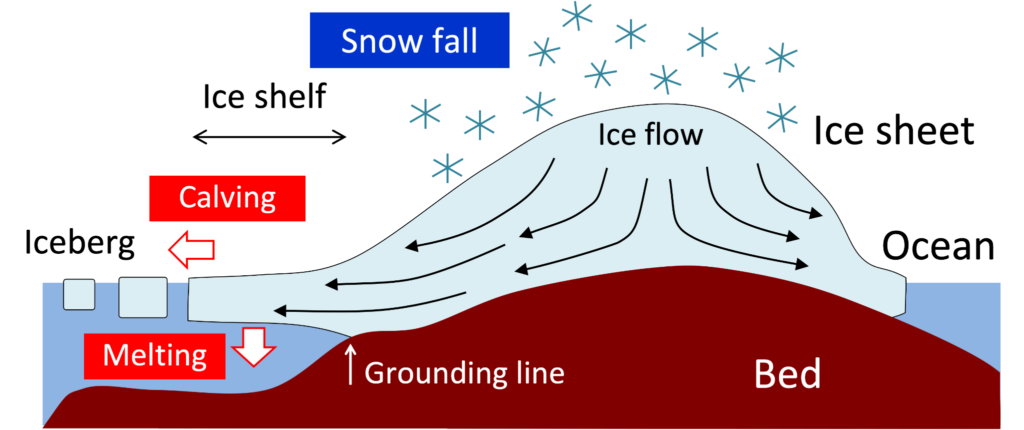

In recent decades, the mechanisms behind the rapid melting of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets have become clearer. We have learned the importance of “location” because rapid melting occurs where glaciers and ice sheets flow into the sea. In these places, the ice flows out into the ocean at a faster rate. The melting of glaciers is accelerated by contacting the warmer seawater, or by breaking off into the ocean as icebergs.

The mechanisms controlling mass balance of ice sheets. When ice sheets flow along the land and reach the ocean, the bottom of the ice floats in the water due to buoyancy, forming a floating ice called the ice shelf. The flow of the ice shelf is accelerated due to the elimination of friction with the land. In addition, because seawater has a higher temperature than the atmosphere, the melting of the bottom of the ice shelf is accelerated. The ice shelf breaks off and forms icebergs at their terminuses, a process called calving. When the terminuses that held back the outflow of inland ice disappear, the glaciers further flow out faster toward the sea.

In addition, the glacier surfaces are now darkening. The main cause of this phenomenon is the growth of microorganisms such as bacteria and algae. This phenomenon has already been recognized on mountain glaciers in relatively low latitudes, such as those in the Himalayas and the Alps, but in recent years it has begun to occur on glaciers in the polar region of Greenland. When the surface of the ice is pure white, it reflects about 60-70% of sunlight, and glaciers reflect much of the solar energy. However, as the surface darkens, glaciers no longer reflect sunlight, but instead absorb 70-80% of the sun’s energy. This is also one of the reasons why glaciers and ice sheets are melting faster.

A glacier in Greenland with blackened surface due to bacteria and algae (Photo by Shin Sugiyama, 2014)

Short-term changes in glaciers

Studies of glaciers are conducted on a variety of spatial and temporal scales. My research is characterized by a narrower spatial scale and shorter time scale than most other glacier studies. Glaciers are popularly imagined to move very slowly, but the glaciers I often visit for observation move about one meter per day. Using GPS to measure the movement of these glaciers on the scale of minutes, we have observed that they move faster during the day and slower at night.

I want to reveal phenomena that are happening at specific moments in specific locations, such as the moment a glacier collapses and flows faster into the ocean, or how fast it melts in the ocean.

My research on narrow spatial and short time scales may be related to the fact that I originally specialized in condensed matter physics. Since I was measuring small changes that occur in matter on the scale of a thousandth of a second, I believe that studying phenomena that occur on shorter time scales is essential to understand the nature.

Mysteries hidden at the bottom of glaciers.

Drilling survey at Langhovde Glacier, Antarctica, to investigate the bottom of the glacier, from 2021 to 2022 (Photo by Shin Sugiyama, 2022)

My recent research is on calving glaciers, which flow into oceans and lakes. I wanted to study the base of calving glaciers. The condition of the base, where the glacier meets the ground, changes the way the ice slides and flows. It also influences how the meltwater from the glacier flows through the base of the glacier to the ocean. In Antarctica, large lakes have been discovered under the ice sheet, meaning that there are untapped mysteries under glaciers and ice sheets.

I am very interested in knowing what the bottom of the glacier looks like near the terminus of calving glaciers, how it interacts with the ocean and lakes, and if there are living creatures under the ice.

Collaborating beyond expertise

My research on glaciers and ice sheets led me to connect with researchers in various fields, and I gradually began to understand what is happening on the Earth today. I realized that it is necessary to collaborate with researchers in the social sciences to find out what kind of problems climate change will cause for the local people, as well as informing them of our discoveries. We need to accurately research and communicate with local residents about the climate changes that are occurring currently. We also need to go beyond the boundaries of our own research fields and brainstorm with various stakeholders about what we should do in the future.

Hokkaido University has a long history of conducting research in cold regions such as the Arctic and Antarctic; hence, it is a great advantage to be able to conduct research from a broad perspective, collaborating with researchers from diverse fields.

Go visit glaciers!

Both climate and society are changing so rapidly that it is difficult to predict what kind of society and environment we will have 10 to 20 years from now. It is difficult for me to say to young people, “This is what will happen in the future, so please take these steps.” Instead, if you are interested in glacier research, please go to glaciers to see the problems actually happening in the field.

Collecting data only through satellites may cause us to miss things, resulting in preconceived notions that may lead to erroneous explanations. Observing a research subject from space and in the field is similar to looking at an organism from the ecological, cellular, and molecular points of view. It is vital to study a specific subject with multiple different approaches. In addition, research techniques will evolve in unforeseeable ways. I hope that you will challenge yourself to do research using new technologies, and do the best you can at that time.

A roundabout routeI studied condensed matter physics at university, and after completing graduate school, I joined a company in Gunma Prefecture where I engaged in research and development of optical fibers. I immersed myself in research on weekdays and went to the nearby mountains every weekend. While leading such a life, I began to realize that I wanted to do research related to nature and mountains. I decided to try my hand at glacier research, thinking that I could apply my knowledge of condensed matter physics to ice. After resigning from the company, I did not immediately pursue a research career, but instead joined the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) for two years. I worked as a high school science and mathematics teacher in the Republic of Zambia. During my time there, I taught two or three daily lectures on physics and mathematics in English. I feel that my efforts to make people understand differential-integral equations in math and motion equations in physics — which is a difficult task, even in Japanese — led to my current resolution of trying to explain my research in an accessible manner. |

Written by Space-Time Inc.

Part of the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change