This article was published in Japanese in Litterae Populi magazine (Autumn 2025, Vol. 75)

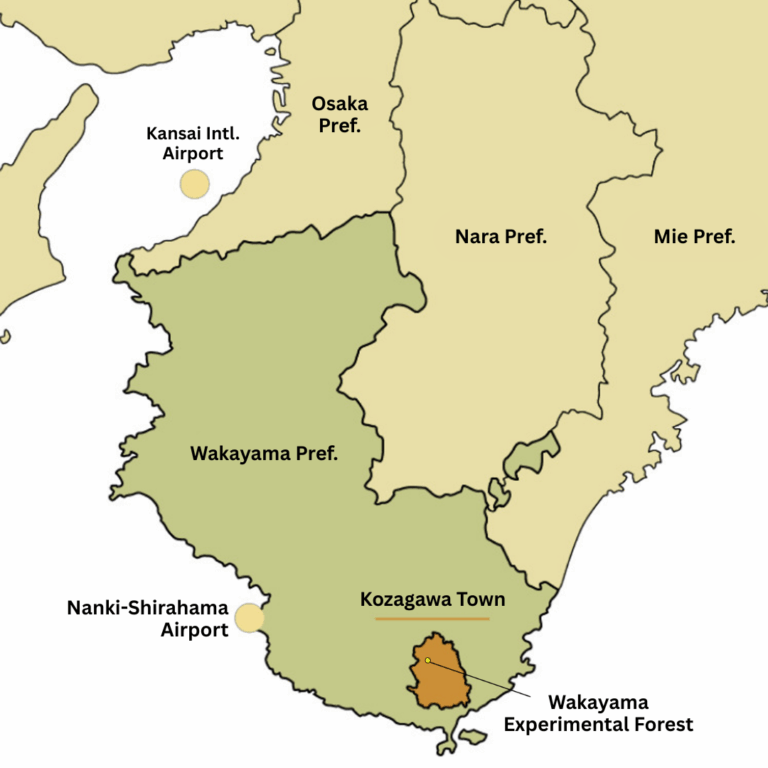

Hokkaido University’s only research forest outside Hokkaido, the Wakayama Experimental Forest (Field Science Center for Northern Biosphere), was established in 1925 in Kozagawa Town, Higashimuro-gun, Wakayama Prefecture, and it celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Serving as a field for forest science research and education, it has fostered many students, and its various community-rooted activities have cultivated a bond between the forest and the town over the past century.

The Only Hokkaido University Research Forest Outside Hokkaido

Located in the Hirai district of Kozagawa Town, in the southern part of the Kii Peninsula, approximately 1,800 kilometers southwest of the Sapporo campus, Hokkaido University’s Wakayama Experimental Forest is the only one among the university’s seven research forests that lies outside Hokkaido. In the 1900s, when domestic demand for construction timber increased, the university called upon the National Governors’ Association to provide land for education and research concerning warm-temperature plantations of Japanese cedar, Japanese cypress, and other species. Wakayama Prefecture responded to this call, leading to the establishment of the experiment forest in 1925.

Abundant Tree Species Fostered by a Warm, Humid Climate

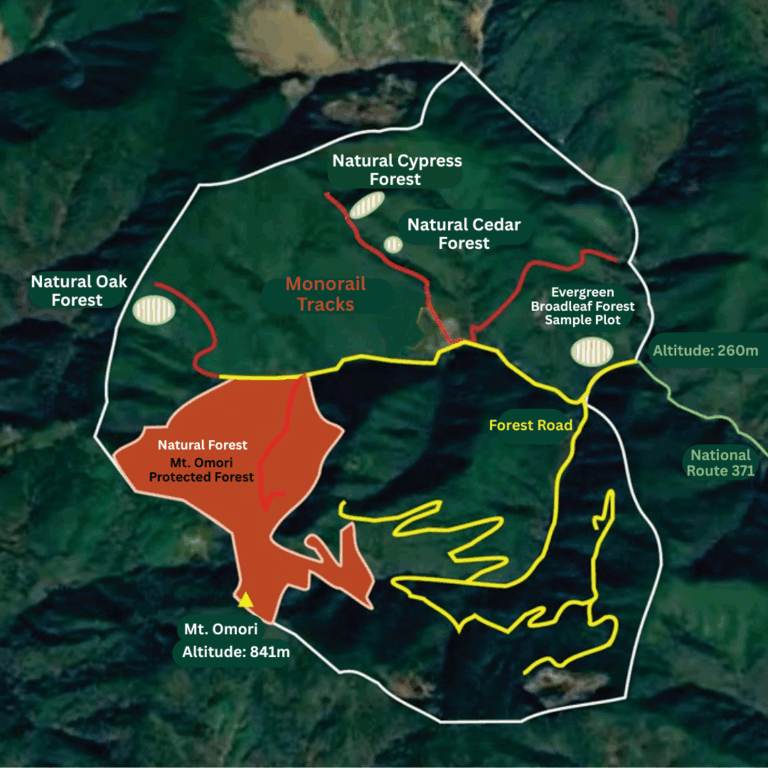

The forest covers approximately 450 hectares, about 96 times the area of the Tokyo Dome baseball stadium. The region’s average annual temperature is about 15 degrees Celsius, and the moist air that flows in from the Pacific Ocean brings heavy rainfall when it encounters the slopes of the Kii Mountains. With annual precipitation of approximately 3,300 millimeters, it ranks among Japan’s highest rainfall areas. This warm, humid climate nurtures 180 species of trees that flourish throughout the forest, a remarkable diversity that never fails to amaze visiting experts. Approximately 80% of the forest area is covered with plantations mainly of Japanese cedar and Japanese cypress, while the remaining 20% supports natural forests of evergreen broad-leaved trees such as Japanese chinquapins and evergreen oaks. The rare Japanese umbrella-pine (Sciadopitys verticillata), a member of the pine family, also grows naturally here. Due to its resistance to water and decay, Japanese umbrella-pine timber has been used for the roofs of historic buildings. Additionally, the Hirai River, which flows through the experimental forest, has ultrasoft water with few impurities and is home to the Japanese giant salamander, Japan’s largest amphibian.

Monorails Leading into a Mystical Forest

-768x456.jpg)

(Drone photography: Hiroki Ito, Geograms Co., Ltd.)

A notable characteristic of the Wakayama Experimental Forest is its range of elevations. The forest entrance sits at 260 meters above sea level, while the summit of Mt. Omori, the highest point, is at 841 meters, an elevation difference of approximately 600 meters. Given that steep slopes exceeding 30 degrees cover 70% of the area, monorails are utilized for efficient movement throughout the mountain. Laid on the steep slopes are four monorail lines totaling three kilometers in length, with railway cars that slowly climb through the trees while receiving sunlight filtered through leaves.

The Wakayama Experimental Forest welcomes approximately 2,000 visitors annually, serving not only students and researchers but also local elementary school students for educational purposes. Professor Osamu Kishida, Director of the forest, proudly states, “Using the monorails, children and elderly people alike can easily access the natural forests near the summit of Mt. Omori, where Japanese umbrella-pines grow naturally. I think it’s truly unique that anyone can experience a forest that’s been preserved untouched for 100 years.”

Another distinctive feature of the Wakayama Experimental Forest is its wooden administrative building, constructed in 1927. This two-story Western-style building, with its striking blue roof and white walls, was designated as a National Tangible Cultural Property in 2013. Equipped with lecture rooms and accommodation facilities, it serves as a base of operations for researchers and students. The building’s reference room displays insect specimens and stuffed animal specimens of species that inhabit the forest, as well as specimens of various trees. With leaves, branches, bark, and fruits that comprehensively represent the region’s vegetation, the building serves as a hub that helps pass forest knowledge on to future generations, utilized not only for student educational training but also for experiential learning programs for elementary students and the general public.

Learning from the Forest, Living with the Forest

The warm, humid climate and steep terrain create forest ecosystems that differ completely from those in Hokkaido. This forest supports research in numerous fields, including forest ecology, with a variety of observation equipment installed within it. One such structure is the “jungle gym.” Resembling children’s playground equipment but built as tall, massive scaffolding, it was installed to provide researchers with easy access to the tree crowns. It is used for monitoring tree growth by enabling evergreen broad-leaved tree leaves to be observed from above and litter traps to be installed for the collection of fallen leaves.

In the Japanese cedar and cypress plantations, research is also conducted on how different thinning widths affect soil dryness and rainfall-induced sediment movement. Plantations left unmanaged without proper interventions, such as thinning, become overcrowded with trees that fail to develop adequate root systems, making them vulnerable to natural disasters like landslides. Indeed, a large-scale landslide occurred in 2024 near the plantations in the Hirai district, and the national route leading to the Wakayama Experimental Forest remains closed. The sections buried in sediment are impassable by car, and accessing the forest requires walking along alternative routes. Director Kishida explains, “Japan has many plantations, and natural disasters from climate change are imminent threats.” The research conducted at the Wakayama Experimental Forest provides crucial knowledge that contributes to national forest policy and ecosystem conservation.

As a Field for Community Collaboration

。(ドローン撮影:GEOGRAMS-伊藤広大)-768x432.jpg)

In February this year, Hokkaido University’s Wakayama Experimental Forest and Kozagawa Town collaborated to implement a Freshman Seminar (intensive course) for first- and second-year students from all departments. While seminars centered on the experimental forest had been held previously, the cooperation of townspeople enabled new additions, such as hunting, allowing students to learn more deeply about actual town life. Not only did the 18 students who participated in the four-night, five-day program tour the experimental forest, but they also took part in the daily activities of townspeople, including cleaning irrigation channels, clearing out abandoned houses, and managing wildlife damage.

Students Experience a “Marginal Community”

Nestled in a serene landscape of terraced rice fields and beautiful, clear streams, the Hirai district of Kozagawa Town, where the Wakayama Experimental Forest is located, faces the serious realities of aging and depopulation that quietly permeate the area. With 69 residents in 2024 and an average age of 73, the Hirai district represents what is known as a “marginal community”—a rural area where more than half the population is 65 or older. Students interacted with residents through various life-related experiences, including harvesting hassaku oranges, repainting a shrine torii gate, pruning yuzu trees, and helping residents build chicken coops.

Momoka Kato, a second-year student in the School of Fisheries Sciences who participated in the seminar, recalled being particularly impressed by cleaning out the fallen leaves and mud that had accumulated in the approximately three-kilometer-long irrigation channels that bring water to the rice paddies to ensure water flow for the spring rice planting. Kato reflected, “We divided the work among 18 students over three days, but it was challenging, as the heavy mud and muck put strain on our backs and arms. Realizing that the elderly residents of Kozagawa Town must handle this physically demanding task made me acutely aware that labor shortages are a serious problem.” Kosuke Matsuda, a second-year student in the School of Agriculture who experienced not only the challenges of mountain village communities but also their appeal through interactions with residents, smiled as he said, “I can’t forget the warmth of the people and how delicious the food was. Wherever we went, residents always called out to greet us, and the local cuisine and wild boar hot pot that the locals treated us to were truly delicious.”

Century-Long Bonds Between the Experimental Forest and the Community

Kengo Nakamura, who promotes collaboration between Hokkaido University and local governments as a Specially Appointed Associate Professor in the Office of Public Relations and Social Collaboration, was involved in running this seminar. He reflects, “Witnessing firsthand a community with strong connections and bonds between people and between people and nature, where everyone helps and influences each other, provided significant stimulation for the current students.” He also noted, “While the residents warmly welcomed our students, I felt this was possible only because the Wakayama Experimental Forest has been part of the Hirai community for a full 100 years, having created deep, long-standing bonds of trust.”

On the final day of the seminar, students presented their observations about challenges facing mountain villages and proposals for long-term student stays to residents and town hall staff. Hayato Amata, a second-year agriculture student who presented on the newfound interest in managing wildlife damage that he had developed through hunting, said with a sparkle in his eyes, “The local hunting association members’ thoughtful approach to life made a deep impression on me, which sparked my tremendous interest in ecosystem management.” He plans to recruit volunteers from seminar participants to return for extended stays in the Hirai district to help solve local community issues. “I strongly feel that student power is needed in this area. My current goal is to create a system for students to visit the Hirai district sustainably,” Amata says, looking toward the future.

The Future of a “Forest of Co-Creation”

Director Kishida earnestly hopes that through training at the Wakayama Experimental Forest, students will come to view regional realities as their own concerns, deepen their perspective on society, and develop into people who can create a better society. He emphasizes, “This is also crucial for preserving forest-based educational and research sites.”

At 100 years, the Wakayama Experimental Forest has distinguished itself not merely as a research facility but also as a community-rooted “forest of co-creation” through its deep bonds with Kozagawa Town. As a place where students can gain firsthand insights into the relationship between forests and people that cannot be learned from textbooks, the Wakayama Experimental Forest will continue weaving its historical narrative into the future.

Related Content

Fields of Knowledge—Wakayama Experimental Forest: A Hidden Forest with Verdant Greenery

-1024x608.jpg)