This article first appeared in the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change.

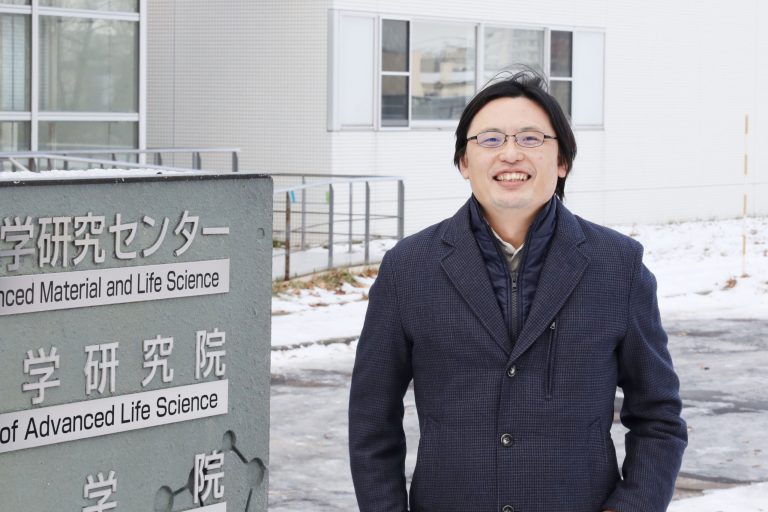

The extent of summer sea ice in the Arctic Ocean has decreased by about two-thirds over the past 35 years, and temperatures in the Arctic are rising about four times faster than on the planet as a whole, affecting not only the globe’s natural environment but also human society, culture, politics, economy, and international relations. Fujio Ohnishi, Associate Professor at Hokkaido University’s Arctic Research Center spoke to us about international relations in the Arctic region.

Diverse cultures in the Arctic Region

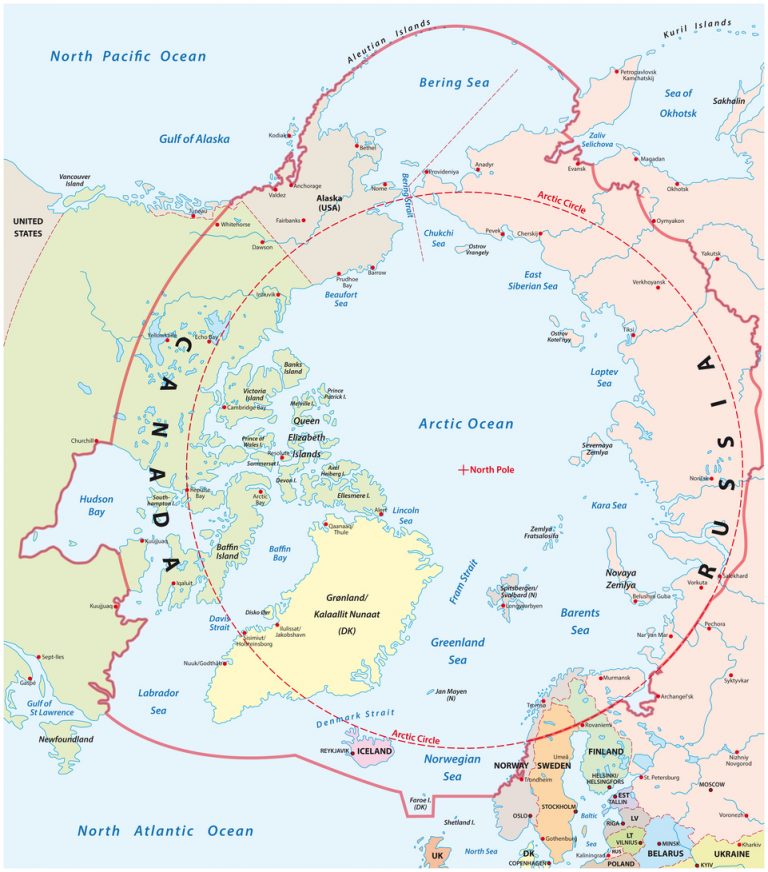

There is no unified definition of the Arctic region. Some astronomers define the Arctic region as the area north of 66°33’ north latitude (the Arctic Circle zone), while others define the Arctic region in terms of temperature and vegetation. The eight countries whose territory fits many of these criteria are the USA (Alaska), Canada, Russia, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark (Greenland) and Iceland, which are usually referred to as the Arctic region.

When most people think of the Arctic, they may typically imagine majestic wilderness, icebergs and polar bears, but in fact, the region is home to some four million people. Moreover, it is a place of different nationalities and various indigenous peoples, with a wide variety of ways of life, and a range of political systems and economies.

I research the state of international relations in the eight countries in the Arctic region by reviewing the literature and conducting interviews. For example, I interview diplomats, people from international cooperation organizations, business people and indigenous people in these countries, and exchange views with researchers working in the Arctic region.

The unique Arctic Council

In 1987, before the end of the Cold War, General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union made a speech in which he called for the Arctic region to become a place for international cooperation and peace. In response, in 1996, eight Arctic countries established an organization for international cooperation called the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council plays a very important role in Arctic governance and has established various rules and regulations. The Japanese media often portray the world’s countries as competing for Arctic resources, but in fact this is not the case, and orderly and cooperative international relations have been in place based on the guidelines of the Arctic Council.

The Arctic Council was originally involved in two areas of international cooperation—conservation and protection of the environment, and sustainable development—and, in recent years, it has also been working on ways to help local communities in the Arctic to adapt to severe climate change. Ministers from the member states meet biennially to set policies for emerging issues. A unique feature of the Arctic Council is that representative organizations of indigenous peoples are guaranteed a voice in decision-making. There is no other intergovernmental cooperation body where the representatives of the state and the representatives of indigenous peoples are designed to sit together at the same table to speak and decide things. It is a very advanced model.

International relations in the Arctic are changing due to global warming

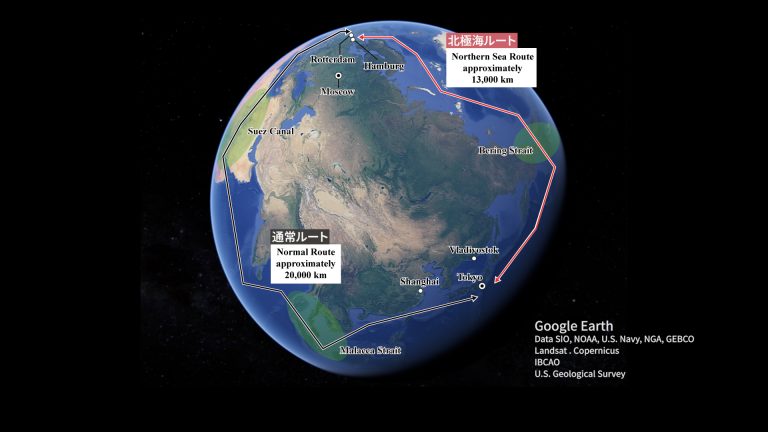

The significant reduction in the summer sea ice extent in the Arctic Ocean in the 21st century due to global warming has led to expectations of economic activity in the Arctic region that were previously infeasible. For example, goods are transported between Europe and Asia using the southerly Suez Canal route, but if the ice melts and the Arctic Sea route can be used in the future, the travel distance will be reduced to two-thirds. This will have a particularly large impact on trade between Asia and Europe, including Japan. The exploitation of resources such as natural gas and rare earths in the Arctic region has also attracted attention.

There is also a high sea in the middle of the Arctic Ocean called the Central Arctic Ocean, which is considered the common property of mankind, including the seabed part. Some people believe, for example, that if fish migrate northwards into that area in the future, a fishing industry may be possible, while others believe that with the development of technology, resource exploitation may be possible on the seabed at a lower cost. The widening of the various economic potentials has suddenly made international relations in the Arctic more active, and many scholars of international relations and international politics, such as myself, have turned to the Arctic as a subject of study.

Climate change has also brought changes to the livelihoods of people who originally lived in the Arctic region. For example, the melting of the ice has changed irregularly from year to year, so the routes that have been handed down as traditional knowledge from generation to generation by the Inuit and other hunters are no longer valid. The Arctic Ocean coast also began to experience tidal surges not seen before, leading to coastal erosion and forcing some people to leave the land they had originally inhabited. Changes in the natural environment have also had an impact on the socio-economy, causing compounding changes in many areas.

Arctic research in Japan

With the exception of pre-war North Sea ice observation voyages by the Ministry of Agriculture, Japanese Arctic research began in 1957 when Ukichiro Nakaya—a scientist famous for creating the world’s first artificial snowflakes and who had previously worked at Hokkaido University—took part in snow and ice observations in Greenland. Following this, observation research by individual researchers and research institutions became the mainstream. Since the 2000s, it has gradually become clear that climate change in the Arctic region can cause abnormal weather in Japan. There are important economic implications for Japan as well, such as the utilization of Arctic shipping routes. Therefore, in 2011, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology launched the Green Network of Excellence project, making Arctic research one of the national projects.

Currently, with the aim of realizing a sustainable society, the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability II (ArCS II) project (2020-2025) is underway, led by three organizations: the Hokkaido University, the National Institute of Polar Research (NIPR), and the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC). While the focus will continue to be on natural science research in the Arctic region, in one of the major projects, researchers in international law and international relations will gather knowledge and provide it to domestic and international stakeholders as a basis for the formation of international rules in the Arctic. I am responsible for the research program on international relations and continue to conduct research that leads to policy recommendations.

Precarious ‘symbols of peace’

An important key phrase for international relations in the Arctic region is the term ‘Arctic exceptionalism’. This term refers to the belief that international cooperation should continue in the Arctic region, even if, for example, war breaks out outside the Arctic and political tensions between states rise. When Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and the Ukrainian crisis broke out, Western countries and Japan simultaneously imposed economic sanctions on Russia, which strained international relations. However, the eight Arctic states, including Russia and the USA, did not suspend the Arctic Council. This was because they had decided that they could not stop the activities of the Arctic Council, which discusses adaptation measures in the Arctic region, where climate change is accelerating at a rate four times the global average.

However, in February 2022, Russia launched a large-scale invasion of Ukraine using military force, which effectively stopped the activities of the Arctic Council, as some countries refused to be present at the same meetings as the Russian delegation. This is the first time in almost 30 years that the activities of the Arctic Council have come to a halt, and Arctic exceptionalism, which has been a symbol of peace in the Arctic region, is dying.

One of the most frequently reported concerns in relation to the invasion of Ukraine is that the Arctic is becoming militarized. There were fears that if all Arctic countries except Russia became members of NATO, conflicts in the Arctic would intensify, but our field research has shown that, at least in the short term, the situation in terms of security has not changed much before and after the war.

However, a situation has arisen where researchers cannot operate on Russian territory. If research cannot be carried out in Russian taiga (coniferous forests) and other areas, for example, carbon budget data cannot be obtained, and it is impossible to calculate how much warming will occur. Furthermore, it has become difficult for people to come and go and do business even for something as mundane as everyday life. There are calls for the Arctic Council, which had proposed solutions to practical problems, to resume its activities as soon as possible.

The Arctic Region is the future of the planet

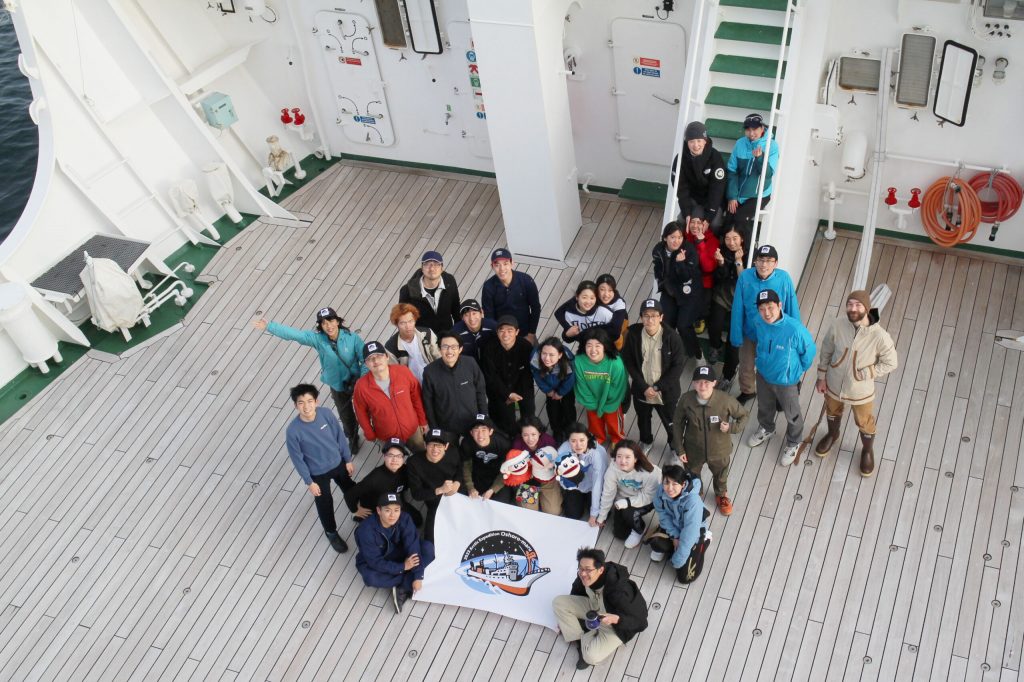

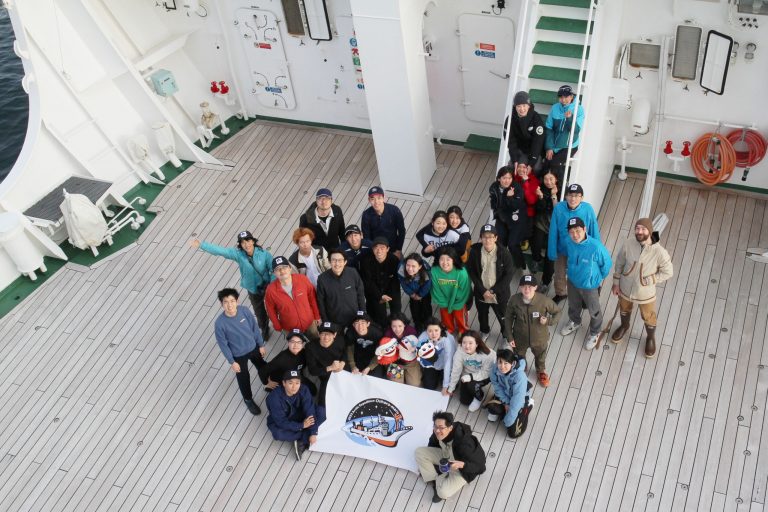

The Arctic region is the future of the planet in the sense that the effects of global warming are progressing at a faster rate than other regions. It is very important for people who do not live in the Arctic region, including Japan, to think about the Arctic region for themselves and do what they can do. I believe that the Arctic region is a place where we can actually see and think about what will happen as a result of global warming, and it is a place where we can learn. The ArCSII Oshoro Maru Arctic voyage in the summer of 2023, which invited students from all over the country as an open training exercise, was a good example of this.

Visit the people and listen to them

International relations in the Arctic is a new research subject that has not yet been fully researched, and it is a real pleasure to explore it on my own. My research is all about visiting the region and listening to what people have to say. There are many different ways of looking at a single issue, so I try to use my feet to understand as much as possible.

In the Arctic region, the scenery is very beautiful. I saw a huge block of ice stranded on the beach in Greenland, which disappeared on the next day. I personally enjoy seeing aspects of nature that I don’t usually see, and it’s a refreshing change of pace. I would love to see young people become colleagues in Arctic research. Of course, people who want to know about polar bears or about Arctic ice are also very welcome, and as I am a researcher in humanities and social sciences, I would be very happy if many young researchers and students are interested in political economy, people’s lives, indigenous people, and things like that.