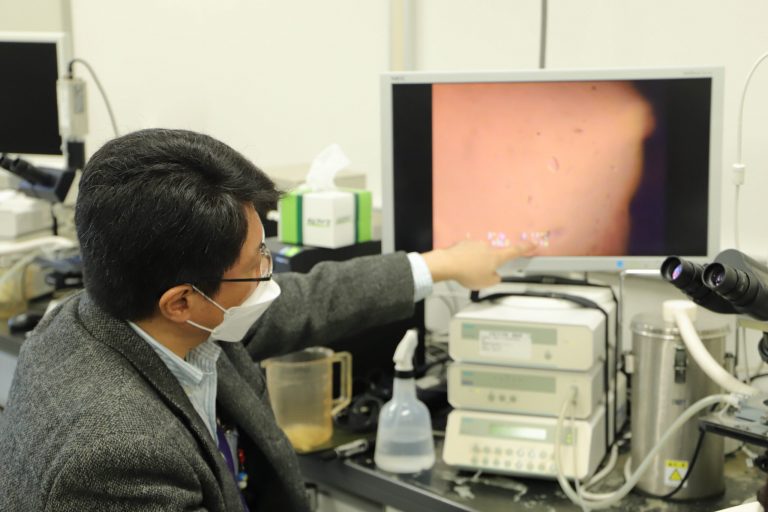

Hidemasa Kondo studied structural biology at the Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hokkaido University (now the Transdisciplinary Life Science Course), and became interested in three-dimensional structure analysis of proteins. He has been conducting research at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) since obtaining his doctorate, and his research concerns is antifreeze proteins.

Collaborative graduate school within AIST

AIST is a research organization designated as a Specified National Research and Development Corporation (特定国立研究開発法人) and is expected to promote the creation, dissemination and utilization of the results of world-class research and development. It was established with the aim of taking advantage of its comprehensive capabilities in diverse research fields to solve social problems ahead of the rest of the world. AIST has centers all over Japan; in Hokkaido, there is the Hokkaido Center in Toyohira Ward, where the Graduate School of Life Science, Hokkaido University, has established a joint graduate school. Dr. Kondo says that the significance of cooperation with Hokkaido University is for human resource development, “AIST conducts research that is close to real-world applications, so students can learn research methods in an environment that is different from a university laboratory.”

What are antifreeze proteins?

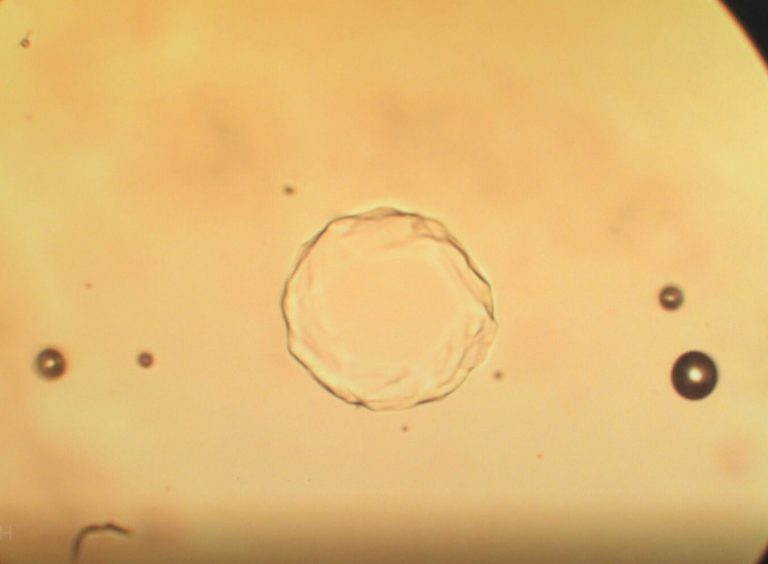

Antarctic fish do not freeze even when the water temperature drops below freezing. Their secret lies in the antifreeze proteins in their bodies. Antifreeze protein is a molecule that binds strongly to the numerous ice nuclei generated in water just before freezing, and suppresses the growth of ice crystals. Without antifreeze proteins, water freezes at sub-zero temperatures, forming large ice crystals that destroy cell structure and disrupt physiological functions. Various types of antifreeze proteins have been discovered, and it is becoming clear that the strength of the ice crystal suppression effect differs by type. In addition to the antifreeze function, antifreeze proteins protect cells by binding to the surface of cells―the mechanism is not well understood.

Using antifreeze proteins to benefit society

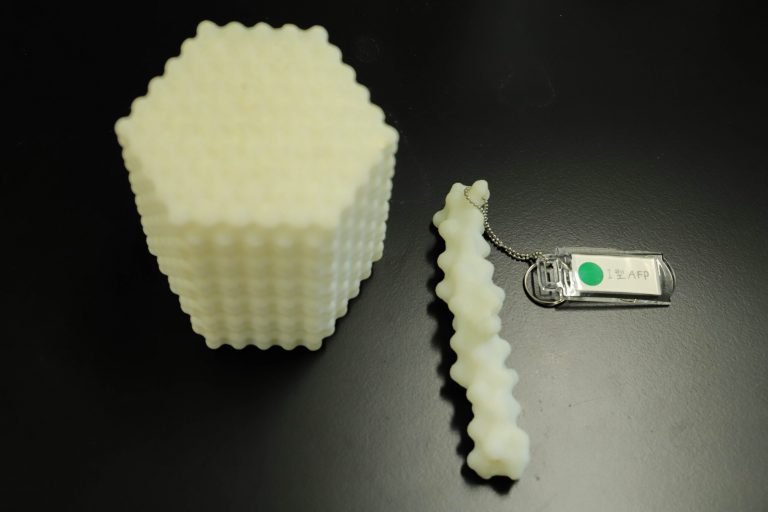

Dr. Kondo’s laboratory aims to clarify the functional principles of antifreeze proteins through structural analysis. They also aim to develop and deploy technology that applies the functions of antifreeze proteins. When cells freeze, it affects the quality of food, etc. Currently, water can be frozen by flash freezing techniques to suppress crystal growth, but the lower temperature required for flash freezing is energy intensive. Using antifreeze protein is expected to keep costs down by reducing energy consumption. Until recently, antifreeze proteins have been harvested from the blood of fish that inhabit polar regions, drawn using hypodermic needles, and consequently was very rare. However, Sakae Tsuda (Kondo’s predecessor, currently affiliated with the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, and a visiting professor at the Graduate School of Advanced Life Sciences, Hokkaido University) discovered that antifreeze proteins can be purified from the muscles of fish that inhabit the coasts of Japan, leading to mass production for industrial use.

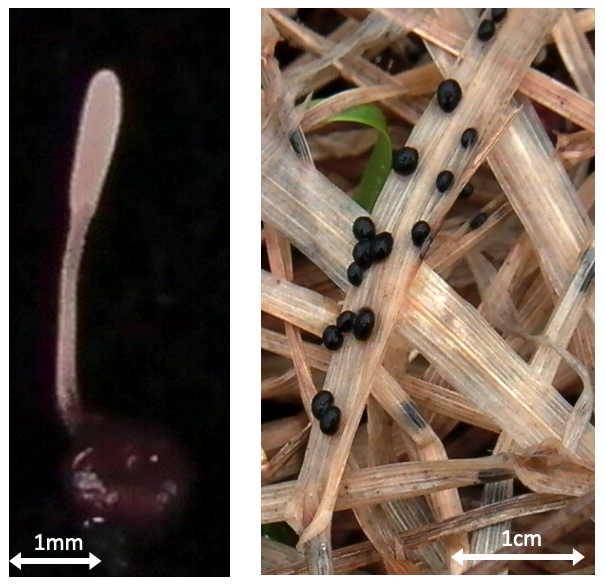

It is now known that antifreeze proteins are also synthesized by organisms such as insects and fungi; Dr. Kondo is researching antifreeze proteins derived from various organisms. Antifreeze proteins derived from insects that live in soil that is colder than ice have a strong antifreeze function, and fungi for which culture methods have been established are easy to produce. The current research goal is to extract it from edible microorganisms, which could produce antifreeze proteins that are highly safe and can be added to food. In addition, antifreeze proteins are expected to be used not only in the food industry, but also in cold storage technology for office buildings and cell preservation solutions in the medical field.

Message to students

Dr. Kondo’s motto is “pursuit of truth.” The various antifreeze proteins have similar functions, but they often have different three-dimensional structures. The goal of his future research is to elucidate as many of these mysteries as possible. “It may be the same with other research, but it is most interesting when we are able to discover a three-dimensional structure that no one has ever seen before, or when we are able to grasp new characteristics,” he says. He says that it is important for students starting research to be able to express themselves with broad perspectives,“I want each student to become a person who can talk not only about experimental techniques and objectives, but also about the content and dreams that derive from them.”

Diverse research group

The Kondo laboratory has students not only from the School of Life Science, but also from the School of Science, as well as international students from Germany and China. They accept students with diverse backgrounds. “AIST has extensive facilities and active joint research with companies, conducting research that will benefit society. That’s what makes it attractive,” says a student in the laboratory.

If you are interested in research that can give back to society, in an environment different from that of a university, AIST’s joint graduate school welcomes you!