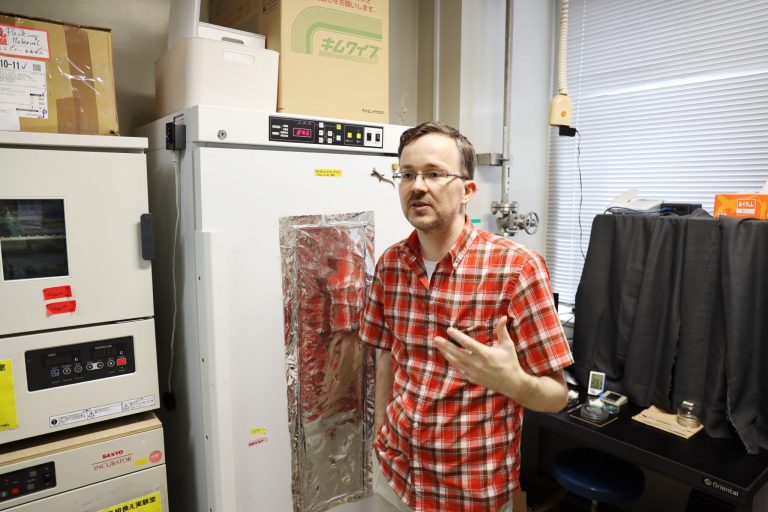

Hokkaido University’s science program for international students, the Integrated Science Program (ISP), is quickly becoming one of the most sought-after English degree courses in Japan. Coming from Germany, Assistant Professor Michael Schleyer is the latest addition to ISP’s diverse faculty roster. His current research focuses on memory, decision-making, and locomotion in Drosophila larvae using an innovative behavior analysis software that he developed.

When Albert Schweitzer said, ‘Happiness is nothing more than good health and a poor memory,’ some bugs took it seriously. In particular, Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) larvae form rather simple memories that are short-lived—making them an easy model to study learning and memory formation. It is exactly this characteristic that Schleyer has been taking advantage of to study how previous experiences affect decision-making.

“I’m intrigued by how the brain organizes behavior, and how memories influence decision-making. I want to know which neurons are responsible for which behavior. While the human brain is too big and complicated, the brain of Drosophila larvae is comparatively simpler. It has only 10,000 neurons and each of them can be individually controlled, making it easier to study,” explains Schleyer.

Manipulation of individual neurons is easy, thanks to the modern technique of optogenetics—a method that uses light to trigger or inhibit a neuron using light-sensitive proteins. “We activate the neuron and observe the behavior of the fly, or we silence the neuron and observe which part of the behavior is impaired.”

Dopamine neurons are famously involved in the reward and punishment system of the brain. Lesser known, however, is their contribution to motion control. “For example, the uncontrollable movements seen in Parkinson’s disease are linked to dopamine neuronal loss. But very little is known about their role in insects. Our recent findings show that Drosophila maggots start bending upon artificial activation of dopamine neurons. I am interested in finding out if the neurons responsible for the bending are the same as those involved in the reward-punishment circuit or those with learning and memory,” said Schleyer. “The dopamine system works in similar ways across the animal kingdom, which means understanding Drosophila brains brings us one step closer to understanding ours.” These findings were recently published in the journal Open Biology.

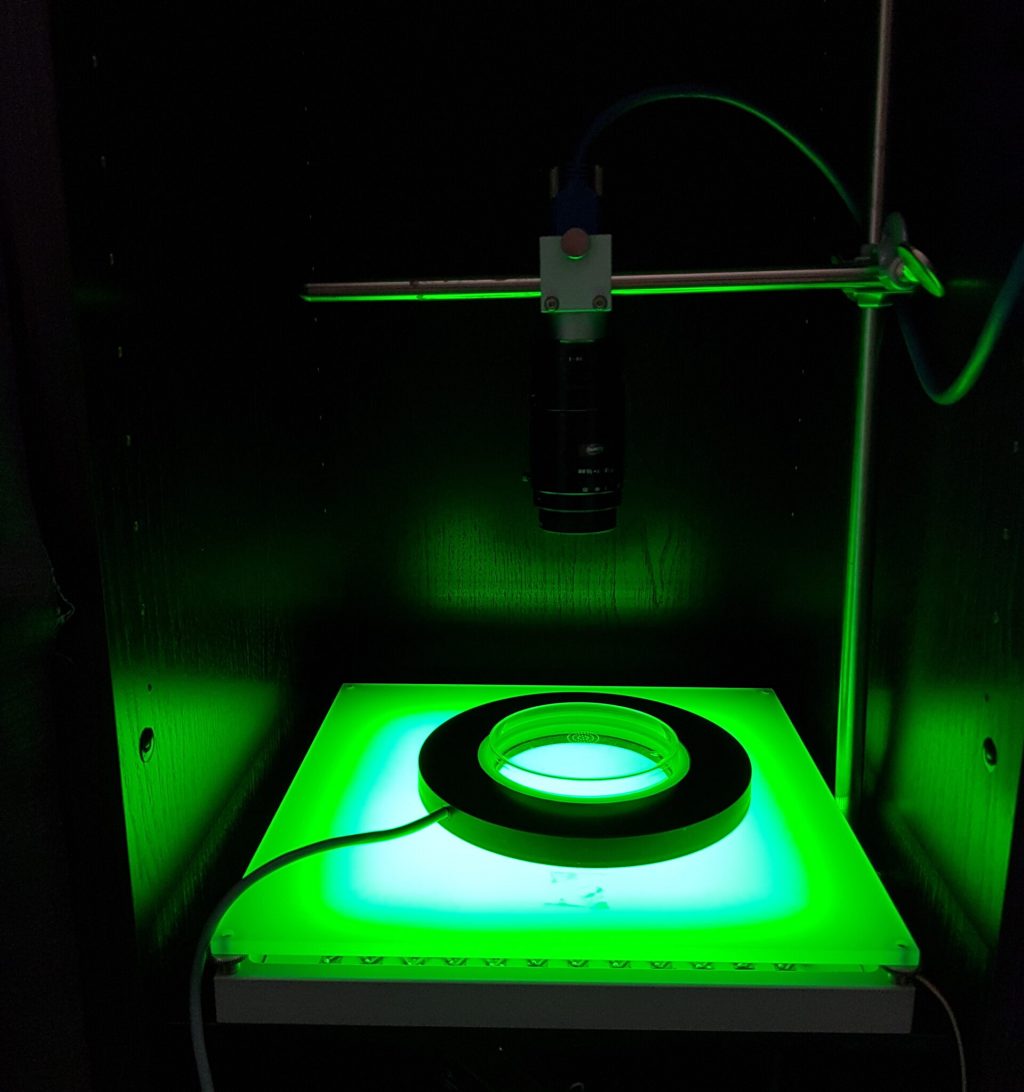

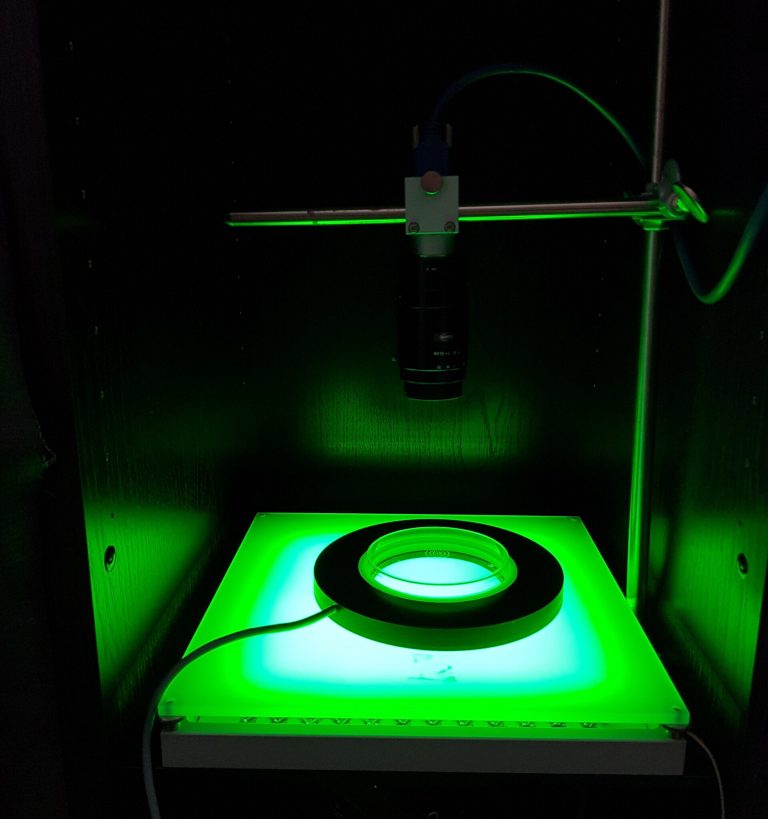

Schleyer is also credited with developing a game-changing behavior analysis tool for Drosophila larvae: the Individual Maggot Behavior Analyzer (IMBA). “With no visible individual traits, Drosophila larvae are almost indistinguishable from one another, making it hard to track individuals within a group. Unlike other software, the IMBA uses a computational contour-based model to distinguish between individuals, preserving their identities even after collisions,” explains Schleyer. “It calculates more than 90 attributes for each animal and presents plots and graphs for detailed analysis.” The software is free to use and does not require any specialized hardware, just a camera placed above the animals. IMBA is pushing the boundaries for maggot behavior analysis and is quickly gaining popularity in the scientific community.

Curiosity might have killed the cat, but it always wins the battle against fear, unlocking doors and leading to new discoveries. Schleyer’s journey started when he questioned the dominant view about how dopamine neurons work in Drosophila larvae. “I was told that dopamine neurons signal if the stimulus is ‘good’ and ‘bad’—if an odor is good or not, for example—but they can’t distinguish between two ‘good’ signals, like tasty food and good odor. That seemed strange to me, and I didn’t agree with this idea. It took me several years to prove that dopamine neurons can indeed differentiate between the ‘quality’ of good signals, and I consider it as one of my biggest achievements,” Schleyer says with a smile.

The question he had as an undergraduate student in a practical course led him into this field, and he hasn’t looked back since. “That’s what I love about science—it is never boring. It fulfils the natural curiosity drive and is extremely rewarding. My message to anybody interested in science is to be curious and stay curious.”

As a Principal Investigator at his new lab in the Faculty of Science, he is also supervising other projects that aim to understand the Drosophila brain, its behavior, and the underlying neuronal mechanisms. Research is conducted on a wide range of topics, including larval learning, the effects of sugars on memory retention and stability, and the role of amino acids in how larvae search for food and form parallel memories, amongst others. More information can be found at Schleyer’s website.

From undergraduate students to interns to post-doctoral researchers, the Schleyer lab is tackling the brain, one larva at a time.

Researcher’s contact details:

Michael Schleyer

Assistant Professor

Institute for the Advancement of Higher Education

m.schleyer[at]oia.hokudai.ac.jp