This article was published in the Spring 2023 issue of Litterae Populi. The full issue can be found here.

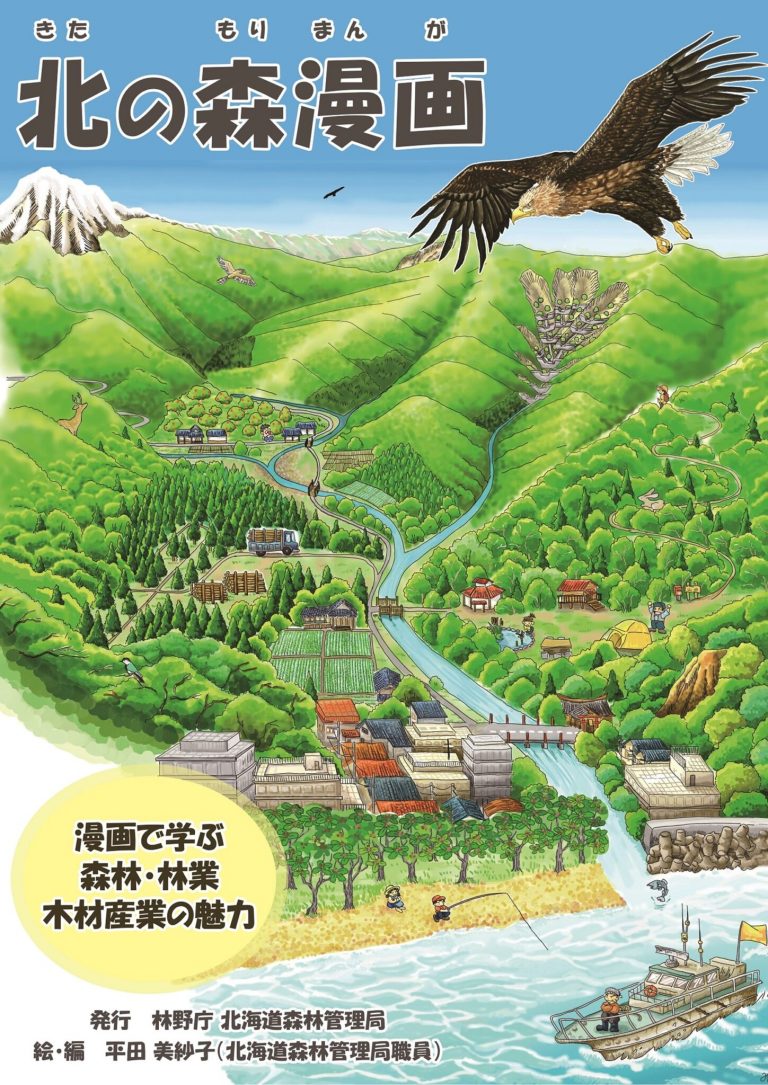

Misako Hirata aspires to become an “interpreter” and “cheerleader” of forestry using her illustration and cartooning skills based on her frontline experience as a forester at the Forestry Agency. The bold composition of her illustrations is fascinating, and her cartoons with humorous dialogue warm the hearts of readers. She works earnestly as a cartoonist at the Forestry Agency, and discussed her interests since her school years and her motivation to continue drawing illustrations and cartoons in an interview.

Misako Hirata

Manager, Management and Planning Section, Planning Division, General Affairs and Planning Department, Hokkaido Regional Forest Office, Forestry Agency.

Graduated from the School of Agriculture and the Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University.

Misako Hirata was born in Hokkaido in 1978. After graduating from the School of Agriculture at Hokkaido University in 2002 and completing a master’s course at the Graduate School of Agriculture in 2004, she joined the Forestry Agency. She worked as a forester in Gunma and Shizuoka prefectures, and then in the Forestry Agency’s Public Relations Office in Tokyo, before being transferred to the Hokkaido Regional Forest Office. She has also worked as a cartoonist for the Forestry Agency to spread the appeal of forestry to the public.

What was your childhood like?

When I was a child, I loved reading The Insect World of J. Henri Fabre and drew insects and various other pictures.

When I was in the first grade of elementary school, my drawing of a fire engine was chosen to represent my class in a sketching contest. As a girl who had rarely been praised, this incident made me decide to become a painter (laughs). In high school, I had a sense of inferiority, because it was a struggle to study and manage the brass band I headed. Even so, my passion for creativity remained.

What made you enter the Department of Forest Science in the School of Agriculture at Hokkaido University? What did you learn there?

In high school, I was in two minds on whether to become a painter or a biologist. Having studied painting on my own, I decided to study ecology at university and entered the School of Agriculture. There, I was blessed with classmates, 70 percent of whom were from outside Hokkaido, and we hitchhiked across Hokkaido.

At the Department of Forest Science, it came to me as a shock when I learnt about mycorrhizal fungi. While forests support human life through the respiration of trees and the production of wood, it is fungi that support forests. Mushrooms are to fungi what flowers are to plants; the main body of fungi consists of hyphae, which spread around tree roots and in the soil. Fungi have a symbiotic relationship with tree roots. When hyphae extend to other plants, nutrients can be transported to distant trees through the hyphal network. In this respect, forests are a lifeform with interconnecting hyphae under the ground. My excitement at the realization that fungi support the flow of energy throughout the entire earth led me to decide to study mycorrhizal fungi.

While at university, I was impressed by a scene in a virgin forest in the Daisetsuzan Mountains. The forest was full of “corpses,” which was contrary to my childhood impression that forests are full of life and therefore exciting, which I probably developed because my parents often took me camping. In forests, new trees keep growing on top of dead trees over hundreds of years. It was great to feel the endless cycle of death and rebirth.

In relation to your earlier account of mycorrhizal fungi, I wonder if the broad compositions of your illustrations are due to your experience of seeing forests, including the underground, more extensively than most people.

That may be so. I would like to serve as an interpreter highlighting the relatively unknown but commendable parts of forests.

What do you mean by “interpreter”?

I would like to spread the word about the functions of fungi and forestry. I want people to know that forests in Japan are preserved by those working in mountains. I also want forest workers to know the charm of forests and the fact that urban life cannot be sustained without forests. I draw illustrations in the hope that I will become a cheerleader who helps to create more cheering parties for forestry.

How did you acquire the skills to use novel perspectives, such as bird’s-eye view illustrations?

I have no idea. Someone who looked at my illustrations told me that they had never thought of such angles, but these angles come to my mind effortlessly. This may be because I had once read that Fabre used to crawl on the ground to watch insects.

After completing graduate school, you joined the Forestry Agency, didn’t you?

Yes. I also considered a career in research, but my desire to raise public awareness of the charms of forests, including fungi, led me to work for the Forestry Agency. In my second year there, I was appointed as a forester to patrol and survey the national forests. I was assigned to the Forestry Agency’s first project to promote forestry while protecting the natural environment, together with local residents and members of a nature conservation organization in the Akaya Forest located on the border between Gunma and Niigata prefectures. The project involved many people who were familiar with the mountains, and the best I could do was to draw illustrations. Gradually, people began to use my illustrations, and I felt that illustrations could be my weapon.

Is there anything you keep in mind when you draw illustrations?

I make a point of gathering information on site, as far as possible. I also have a specialist, such as a professor at Hokkaido University, take a look at my rough sketches whenever I can. In the beginning, many mistakes were pointed out, such as “Rabbits’ ears face forward when they run.” While it may be challenging to replicate everything precisely, the insights I acquired from visiting field sites myself continue to shape my understanding today.

What are your career aspirations for the future?

My goal in life is to draw an illustration that will remain 100 or 200 years into the future. Even if I, the illustrator, become anonymous, I want to leave one that shows the relationship between living beings and forests. To achieve this goal, I will continue to study and draw illustrations.

Finally, what thoughts or insights would you like to share with the students of Hokkaido University?

Despite the prevalence of online communication, it is important to value in-person interactions. I believe my ongoing pursuit of what I love is what has led me to where I am today. I hope that Hokkaido University students will never be afraid to share what they love and value.

This article was published in the Spring 2023 issue of Litterae Populi. The full issue can be found here.