Impact of sanctions on the Russian economy

March 4, 2022

Shinichiro Tabata

Professor, Slavic-Eurasian Research Center, Hokkaido University

Introduction

This article examines how economic sanctions being imposed on Russia by many countries, in retaliation for its invasion of Ukraine, will affect the Russian economy.

The Soviet Union, and later Russia, have been subject to economic sanctions on a number of occasions. I noted that such economic sanctions have no teeth each time they were imposed. Since economic sanctions require the nullification of economic agreements between two entities, both parties are bound to be affected by them. Strong sanctions are accompanied by major side effects, and the party imposing sanctions often faces countersanctions. In reality, it is difficult to impose sanctions that have a strong impact and, therefore, we generally cannot expect conventional sanctions to have a strong impact. That was my rationale in assessing previous economic sanctions against the Soviet Union and Russia. In fact, there have been almost no cases in which sanctions were able to serve their initial political purpose. But as for the international efforts to sanction Russia, I believe economic sanctions will have teeth if they can restrict Russia’s oil and gas exports. But the countries imposing the sanctions will not be able to avoid major fallout from that.

Simulations on changes in oil and gas exports

In November 2021, we established a study group called “Decarbonization and the Russian Economy” to assess how the global movement toward decarbonization will affect the Russian economy. We have made a number of scenarios for reduced global demand for oil and gas, and have conducted simulations based on them. This simulation model is still very simple and rudimentary, but we used it for estimating the impact on the Russian economy when its oil and gas exports are affected due to sanctions.

As of March 4, no move has yet been made to target Russian oil and gas exports for sanctions, nor has Russia indicated it would restrict their exports as countersanctions. But if Russia’s military invasion continues, it is very possible that such moves will take place.

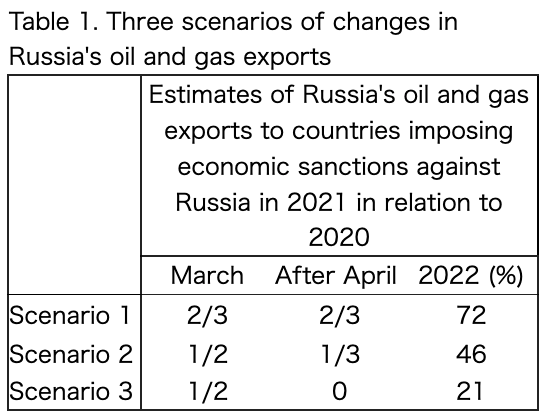

This model estimates changes in oil and gas demand in 2022 compared with the base year of 2020. It assumes that the United States, Canada, the European Union member nations, Britain, Norway, Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand would take part in economic sanctions against Russia. These countries together received 60 percent of Russia’s crude oil exports, 72% of its petroleum product exports and 74% of its natural gas exports. As shown in Table 1, we examined three scenarios of reduced oil and gas exports to these countries. Scenario 1 assumes that oil and gas exports to these countries will be two-thirds of what they were in the base year starting from March 2022, or a 28% reduction in 2022 over the base year. In Scenario 2, exports will be reduced to one-third from April, while Scenario 3 assumes no exports at all from April.

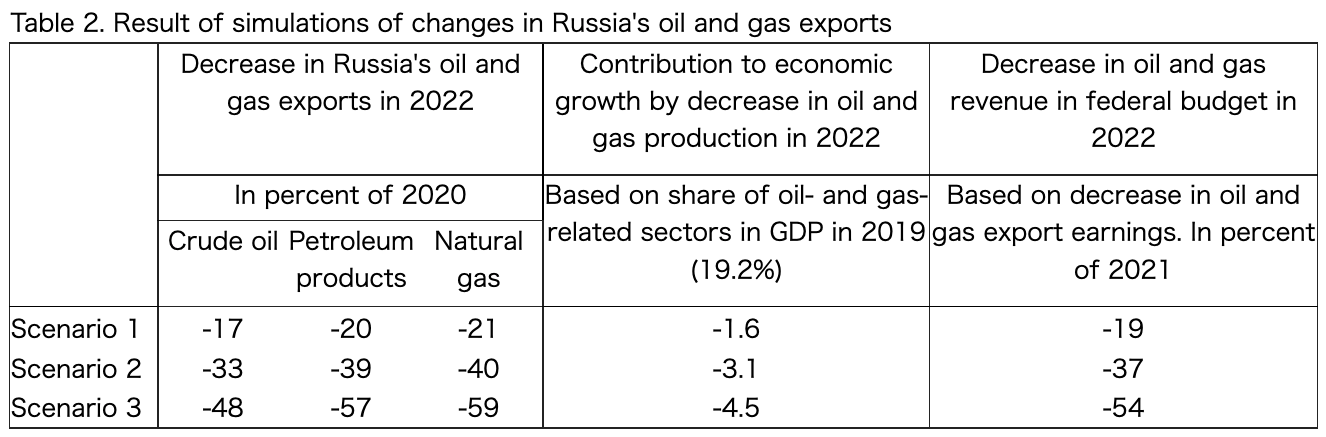

The results of the simulation are shown in Table 2. In Scenario 1, Russia’s exports of crude oil, petroleum products and natural gas to the world are reduced in volume by 17%, 20% and 21%, respectively. Under this scenario, the reduction in oil and natural gas production will push Russia’s economic growth rate in 2022 down by 1.6 percentage points. Also, revenues from oil and gas (mining tax and export tax, etc.), which account for around 40 percent of Russia’s federal revenues, will be reduced by 19% in 2022 over the previous year. In Scenarios 2 and 3, sharper drops in oil and gas exports have a greater negative effect on the country’s economic growth, thus greater rates of decline in oil and gas revenues.

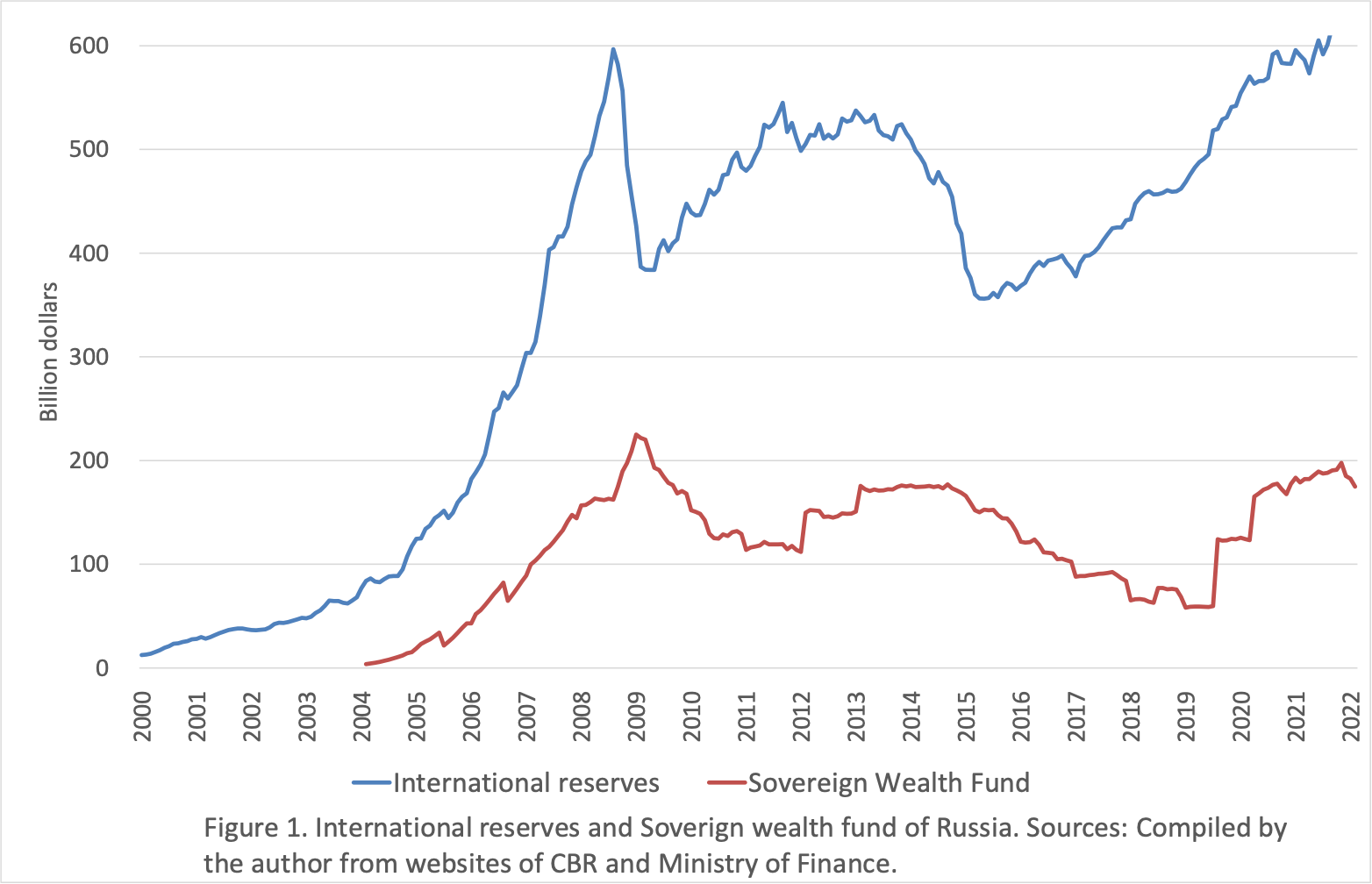

Actually, Russia’s fiscal health is sound. Even in the years when fiscal deficits were recorded, the amounts in the red were equivalent to a mere 3-5% of gross domestic product (GDP). The amount of outstanding federal loan bonds (OFZ) was equivalent to about 12% of GDP at the beginning of 2022. Since Russia established a system in 2004 to put some oil and gas revenues into a sovereign wealth fund (the National Welfare Fund), fiscal deficits have been compensated by this government fund. At the beginning of 2022, the outstanding amount of this fund stood at 182.6 billion U.S. dollars, or 10.4% of GDP, which would allow Russia to withstand several years of fiscal deficits. Russia has been extremely reluctant to make investments with this fund (such as investments in infrastructure), so the outstanding amount of the fund has been increasing since around 2019 (see Figure 1).

Impacts on the ruble’s exchange rate

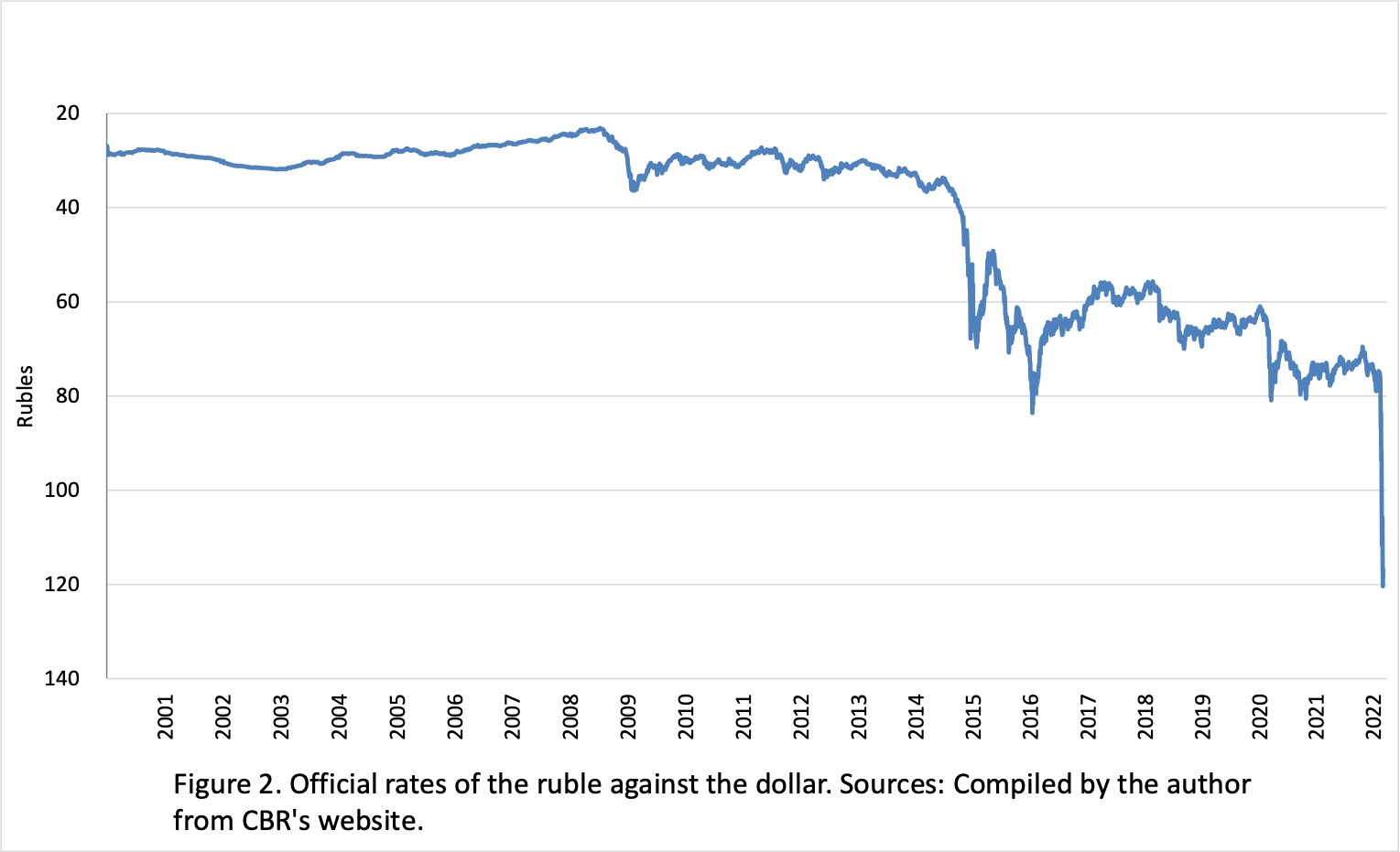

The exchange rate of the ruble plummeted by around 33% as of March 4, and is expected to drop further (see Figure 2). From the end of June 2014 to the beginning of February 2015, the ruble fell due to declining oil prices and sanctions meted out to Russia over its annexation of Crimea. Its value fell by 52%, and the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (CBR) put 102 billion U.S. dollars from the foreign exchange reserve into the currency market to prop up the ruble.

Since then, Russia’s currency exchange management system has gone through a major change, and the CBR has not directly intervened in the currency market since August 2015. Instead, the Ministry of Finance has traded foreign currencies using additional income from oil and gas revenues (the actual trading is done by the CBR). Specifically, when the ministry determined that revenues from oil and gas (the value of oil and gas exports) would exceed projections, it would buy foreign currencies equivalent to the projected revenue surplus. When the revenues did not match the projections, it would sell foreign currencies equivalent to the projected shortfall. Under this system, the ministry undertakes foreign currency trading in advance, because all the additional revenues from oil and gas will later be kept as part of the government’s foreign exchange reserves. Under this system, an estimated 40.7 billion U.S. dollars’ worth of foreign currencies were bought in 2021, resulting in an increase in the amount of foreign exchange reserves. Russia’s foreign exchange reserves have been constantly increasing since 2016, and the sovereign wealth fund has greatly contributed to the increase since 2019 (see Figure 1). Russia’s foreign exchange reserves currently rank fourth in the world after China, Japan and Switzerland.

The Ministry of Finance had planned to purchase foreign currencies due to the trend of rising oil prices since the beginning of 2022, but cancelled the plan on January 24 amid rising tensions over Ukraine. The central bank, meanwhile, announced on February 24 that it would start intervening in the foreign exchange market, and sold foreign currencies worth a total of 1.226 billion U.S. dollars on February 25 and 28. And on February 28, the central bank required companies doing business with entities in foreign countries to sell 80% of the foreign currencies they accrued.

The currency composition of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves is 32% in euros, 22% in gold, 16% in U.S. dollars, and 13% in yuan, according to the latest data available as of the end of June 2021. This shows the diminishing ratio of U.S. dollar holdings since 2017 due to a series of economic sanctions meted out to Russia. It has been pointed out that Russia might not able to easily tap its foreign exchange reserves, besides gold and yuan due to the latest round of economic sanctions.

Conclusions

The main points of this article are as follows:

- When economic sanctions lead to a reduction in Russian oil and gas exports, that will cause considerable damage to Russia’s economic growth and fiscal revenues.

- If the amount of oil and gas exports declines, their revenues will diminish accordingly, resulting in reduced federal revenues in addition to those from value-added tax and corporate tax. As Russia’s military spending is expected to balloon, this raises the question of whether Russia can endure the cost by using the sovereign wealth fund, which is equivalent to 10% of its GDP.

- Russia can earn foreign currencies if it can continue exporting oil and gas. It will thus be able to avert the plunge or continuous slides of the ruble’s exchange rate without selling foreign currencies from its foreign exchange reserves. This is because companies trading with overseas entities are required to sell 80% of the foreign currencies they obtain. But if its oil and gas exports decline in volume, Russia will have no choice but to resort to selling foreign currencies in its reserves.

References

S. Tabata, “Russia solidifying defense: Analysis of its macroeconomic performance in 2020,” Russia NIS Chosa Geppo (Russia & NIS business monthly), May 2021 edition, pp. 2-25. (in Japanese)

S. Tabata, “A Note on the Growing International Reserves of Russia” Eurasian Geography and Economics, Published online: March 1, 2021 [https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2021.1892501].

Shinichiro Tabata is a Professor of the Slavic–Eurasian Research Center (SRC) at Hokkaido University. He is an expert in Russian economy and comparative economics.

Back to the commentary main page